The Peculiarities of European Colonial Slavery’s Legacy in South Africa and the Formation of Slave ‘Dynasties’ at the Dutch-occupied Cape of Good Hope

by Mansell G. Upham ©

I Introduction

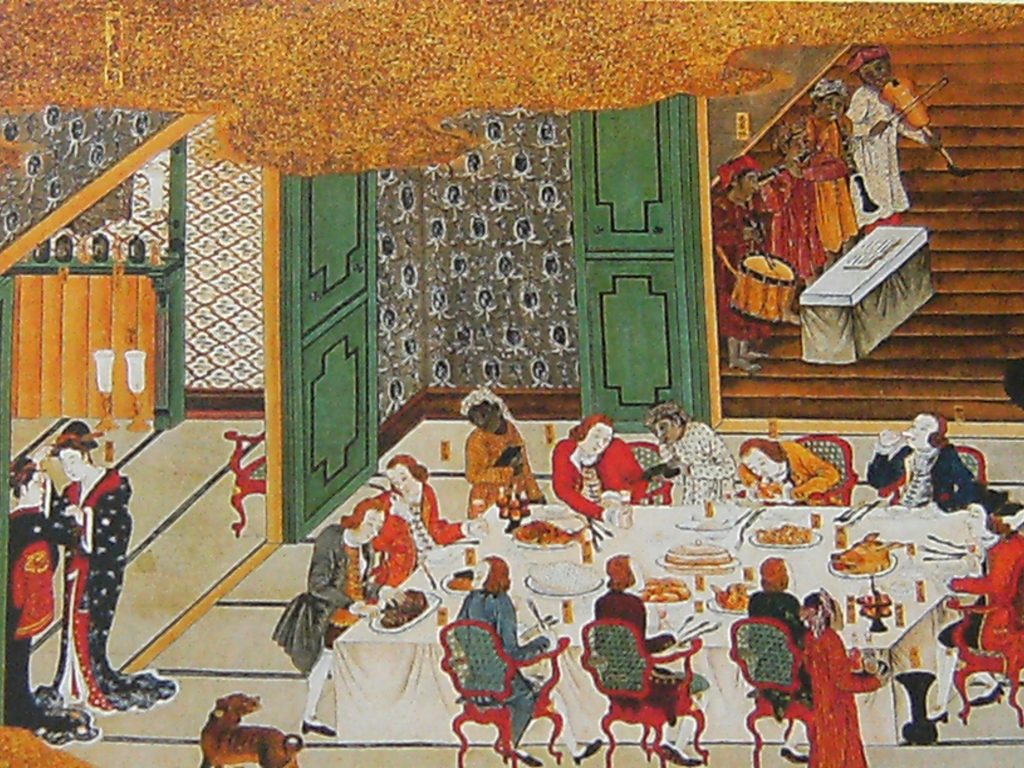

“I am constrained, oh benevolent reader, to receive you to a hastily prepared banquet. Show yourself, I beg you, to be an accommodating and easy guest, and consider these delicacies, such as they eventually are, placed before you as fair and just.“

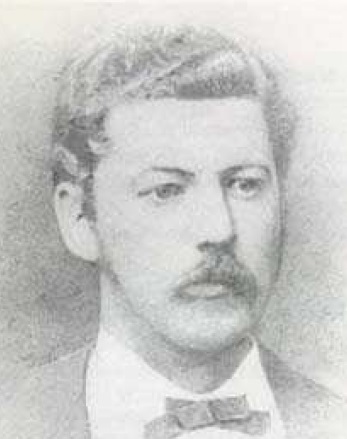

Gysbert Hemmy (1746-1798)[1]

There are two components that I wish to explore in this presentation:

- The Peculiarities of European Colonial Slavery’s Legacy in South Africa

- Slave ‘Dynasties’ at the Dutch-occupied colony of the Cape of Good Hope

II Slavery – now all the rage … Is our Slave history in SA ‘hidden’ or ‘suppressed’?

That South Africa has a hidden or suppressed slave history is not entirely true. There appear to be more records about slave women and homosexual men than anybody else. That the earliest of the first-mentioned just happen to be mostly ancestors to ‘white’ South Africans is not what our governing transformationists are keen, or even willing, to acknowledge. Much of what is mistakenly thought to be hidden, I have summarized before, as follows:

“The slave and Cape indigenous ancestry of old Cape colonial families mostly derives from maternal ancestry. General amnesia, ignorance, presumption, denial and suppression of slave / indigenous heritage – understandable perhaps – presumably goes hand in glove with inherited patriarchal systems and/or perceived misogyny and the repression of maternal descent (not necessarily without female complicity) by the adoption, acquiescence and entrenchment of the overriding convention of carrying over one`s father`s surname and/or adopting one`s husband`s family name. This might explain our hitherto mostly neglected, forgotten and buried matriarchal heritage …“

Eviscerating Van Riebeeck’s Legacy …

Against the backdrop of historical and current increased cultural, ethnic and racial polarization and de-rainbowism, we are now currently witnessing the following fragmentation and political re-alignments:

(1) South African ‘Whites’, in reaction to the more recently defined Woke ideology premised on Critical Race Theory and the brazen and intensified attack on the Afrikaans language means that these folks are again pulling back into the laager – this is akin to so-called African-Americans in hostile denial of actual shared White or European heritage;

(2) South African ‘Coloureds’ (never Coloreds) are divided even more than ever before with some now aggressively promoting a segregationist People of Colo(u)r exclusivity or a hardened, if not militant, reification of Blackness …;

(3) The South African ‘Black’ majority has already politically (as well as institutionally) hijacked the term African replacing it with Black while conveniently still retaining all the other apartheid racial labels.

What is Van Riebeeck’s real legacy?

The answer to this question is simply this: his slave women.

It is these women that become the founders of early slave dynasties at the Cape of Good Hope and who are the subject of this presentation.

III Methodology and Disambiguation – We speak from facts, not theory versus We speak from theory, not facts

Just like there are many genders – the Buginese traditionally have five[2] – we have different (diverse?) types of historical researchers:

- (data-verskrik) genealogists historians

- copy-pasters

- hobbyists

- family historians

- antiquarians

- ‘archival historians’

- institutionalised historians

- heritage acitivists

Of these types of historical researchers, the family historian is hugely constrained ab initio. Salman Rushdie in his Midnight’s Children (1981) succinctly sums up their single-most default:

“Family history, of course, has its proper dietary laws. One is supposed to swallow and digest only the permitted parts of it, the halal portions of the past, drained of their redness, their blood.”

Of all these types of researchers, I am most partial to that of the antiquarian.

Sadly, the term antiquarian has not only become antiquated itself but it has come to be associated with aged fuddy-duddy men such as Casaubon in George Eliot’s mammoth novel Middelmarch. Yet, the definition of the word remains as pertinent as ever and relates to the ideal kind of exhaustive empirical research and critical / analytical writing up thereof as history that I believe is being neglected – even abandoned – more and more in our more modern times:

Antiquarian –

- often used in a pejorative sense, to refer to an excessively narrow focus on factual historical trivia, to the exclusion of a sense of historical context or process. Very few people today would describe themselves as an “antiquary” although the term “antiquarian bookseller” remains current for dealers in more expensive old books, and some institutions such as the Society of Antiquaries of London (founded 1707) retain their historic names.

- an aficionado / student of antiquities or things of the past – more specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifacts, archaeological and historic sites, or historic archives and manuscripts.

antiquarianism = the focussing on the empirical evidence of the past – encapsulated in the motto adopted by 18th-century antiquary Sir Richard Colt Hoare, “We speak from facts, not theory.”

Of the types of historical researchers mentioned above, it is the institutionalised historian – as ideologue incarnate – who is the least credible of the lot. He recalls for me Boniface’s virulent and apt exposure of humbuggery / homboggerij in Cape colonial society[3] and the well-known term ‘all hot air and no substance’. Even now, the invaluable work that genealogists and family historians are doing, is not nearly valued enough by Society in general and the Establishment in particular. The dismal performance (also neglect) by South African historians of VOC history needs especially to be called out here. Nigel Worden’s rationalization [‘New Approaches to VOC History in South Africa’] of what Robert Shell singles out as archival historians – is effectively an exercise in dismissal, denigration and disparagement. It is worth quoting in full:

“… But there was another important characteristic of Afrikaans historical writing on the VOC which limited its broader historiographical influence. Despite differences in subject matter, its approach was overwhelmingly that of empiricism, rooted in Germanic (and Netherlandic) traditions of scholarship in which Afrikaans-language historians were trained.’ 6 Theory and interpretation were eschewed in favour of exhaustive factual recording from primary sources. This is not to decry the latter — indeed the meticulous work of many Afrikaans-language historians has provided a bedrock for later researchers. This tradition continues in more recent key work on the VOC published in Afrikaans, notably that of Dan Sleigh and Karel Schoeman. But the empiricism of such work did not engage with the interests and approaches of historians in the Anglophone world in the 1980s and later, and especially so in South Africa where interpretation and debate had become the essence of historical writing …” [Nigel Worden (2007) ‘New Approaches to VOC History in South Africa’, South African Historical Journal, 59:1, 3-18 (2017)]

It is not clear at all why the free-rider and locked-in-the-present (presentist?) Anglo approach still assumes a ‘superior’ approach. I recall well, too, how horrified I was when a 1st-year history student, Stellenbosch University ‘white’, Afrikaner, male history professors belittling the pioneering work of Anna Böeseken and Margaret Cairns.

Some Pitfalls

At this point, permit me to highlight some pitfalls that bedevil historical research in South Africa.

There is the previously predominant binary nature of South African historiography – very bipolar indeed – but which is now being replaced – by an equally problematic unipolar and Afro(ec)centric ‘Black History’. In short, ‘Blackness’, ‘Black Fragility’, ‘Black Privilege’ and ‘Black Supremacy are now all the rage. Just what is the point of going from one extreme to another? This is surely not the way to ‘restore’ balance. Two wrongs do not make a right. This is for me a quick fix solution inevitably having disastrous consequences.

The seemingly omnipresence of patriarchal tunnel vision (ironically also often reinforced by women), namely the straight / heterosexual pale male whose pathetically last vestige is his singular automatically inherited name.

The unrealistic C.C. De Villiers genealogical system in which families are constructed and written up only in terms of male-line only genealogies.[4]

An American hegemony and post-modernism: history versus relativism. Everything now is being blurred, fudged and conflated – bluf befoeter besef [5], as it were. This induces the indecent haste of what I would term Make up / Catch up / Feel Good History and what is lately reconfigured and termed HIStory / HERstory and ‘lived experience’.

Then, there is the outright (also racist) rejection of ‘white man’s / European history.

The more recent rise and challenge of microhistory to macrohistory as well as current Big Data manipulation (cf. the latest joint project between Stellenbosch and Lund universities – Johan Fourie and Erik Green – in economic history and wealth production and what could easily result in an ideological exercise in ‘restorative justice’), also need urgent re-appraisal.

Colonial, racial and apartheid labels – entrenched and perpetuated – result in a grossly distorted historical reality. An example of this is the racially biased research into the Moravian mission station of Mamre.[6] But not all roads lead to Mamre. This I have pointed out in my own research into the neighbouring Dune folk at Blouberg inhabiting the surrounding farms.[7] The important point here is that both groups are related by blood – studying both groups, separately, perpetuates a distorted historical reality.

Alternative – ostensibly politically ‘corrected’- labels such as Bruin Mense[8], the utterly nonsensical and White Supremacist-re-inforcing People of Colour, and the newly fabricated Cammisa[9], are now being used to ‘restore’ a contentious (real and/or imagined) imbalance by favouring, promoting and perpetuating the separate study of ‘Brown’ (or even more inclusively of ‘Black’) history by way of demonizing, downplaying and marginalizing any previous history expediently deemed to be ‘White’ history and thus irrelevant.

Current attempts to sanitize the past – an example being Khoe and slavery and so-called Camissa affirmation and hagiography. The Cape-born slave woman Zwarte Maria Everts (c. 1663-1713)[10], for example, has been subjected to ‘mis/representation’ for over several decades. The way she is represented ideologically, however, has – tellingly – expediently changed over the years and she has already been transmogrified thricely:

- as a ‘Black’-woman-with-‘White’-descendants

- as a ‘Black’-role-model-for-oppressed-‘Blacks’ that ignores totally her ‘White’ descendants …

and now hopefully – and more truthfully

- as a hybrid-ancestor-of-historically ‘Black’/’Brown’-and-‘White’ South Africans …

Politically contrived, desperate and futile attempts at ‘restoring’ dignity sommer carte blanche – a prime and disconcerting example being that of artist Sue Williams.[11]

“In another extraordinary departure from tradition, local British-born artist Sue Williamson’s state-of-the-art contraption of glass, canvas, water and rope, entitled Memories from the Moat originally exhibited at the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale (1997) is sufficiently in-your-face to challenge any ‘South African’ conscious of her/his slave ancestry. The name of each and every slave purchased and sold at the Cape of Good Hope appearing in the Addendum 2 that originally appeared in Anna Böeseken’s book Slaves and Free Blacks at the Cape 1658-1700, has been engraved on a bottle each, containing also additional information inside. These thousands of bottles, all wet or moist, are either floating and submerged or caught suspended in trawler netting, with water constantly draining through. Bewildered onlookers have the ingenious aid of a Schindler-esque replica of Böeseken’s List in take-away booklet form. Unfortunately, not only has Böeseken’s List been discredited for being substantially inaccurate, the list comprises only those privately owned slaves recorded in terms of Transporten en Schepenkennis procedures and requirements. This means that all the other contemporary slaves that belonged to the VOC (‘the Company’) at the Cape – being the majority of slaves – have been overlooked, ignored: a reconstructed history with a faulty premise.”

Likewise, the new slave memorial slabs in Cape Town’s Church Square consist of slave names copied holus-bolus and arbitrarily from Böeseken’s list and mis-contextualise what has been promoted as an exercise in restoring human dignity but with no regard for any of the actual or real individual identities.

Bottom Line

Surely, it is incumbent on historians, researchers and academics in general – irrespective of all the ‘-isms’ to exhaust the records, even if we decide beforehand that these records cannot be accepted uncritically? One thing is very clear – most historians and academics shy away from unearthing new material or doing primary research.

Why? Invariably:

- they are too lazy – primary research is much too time-consuming and frustrating;

- they omit certain facts – known and new facts do not suit their political agendas;

- they are not competent to access, understand or interpret these records (17th century Dutch, Danish, German etc & 17th century handwriting)

- their knowledge of the VOC-period is disturbingly shallow;

- clichéd and trendy academic constructs are preferred at the expense of trying to establish a larger empirical and scientific understanding.

IV My Modus Operandi

I regard myself as an independent and autonomous scholar-researcher-writer with no public affiliation to any church, academy, organization or institution. I hold that the written record should (be allowed to) speak for itself. I am averse to academic opportunism. In short: if we have to choose between either a top-bottom (prescriptive) versus bottom-top (organic, laissez-faire) approach, I choose the latter.

An example of what happens with the top-bottom approach, can be seen from the following quote:[12]

“… In those days it was possible to change historical understanding by exploring the evidence. The Marxist explanation of the French revolution —also a matter of great concern to the Communist party, which practically monopolised the relevant professorships in France — was overturned by American and British historians. The orthodoxy was that the revolution was carried out by a rising bourgeoisie overthrowing a feudal aristocracy — a crucial stage in the Marxist historical process. But the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ looked in the archives and found it simply wasn’t so: many revolutionaries were nobles; many of the bourgeois were not rising; and there wasn’t much difference between nobles and bourgeois anyway …”

And then we have need to balance the Occidental ‘Big Picture’ with the Oriental devils-in-the-detail approaches. The age-old, ever-applicable, powerful and visceral symbolism of the scales of Justice and ying-yang need not go amiss here.

Working with ‘clusters’ or family networks and principles such as blood-is-thicker-than-water helps to understand wealth, respectability, social censure and marginalisation.[13] And ultimately a due regard for a Holistic approach – in deference to my great-granny’s 2nd (also 3rd cousin) Oubaas (also Kleinneef) Jannie Smuts.

Not excluding, of course, the inestimable value of microhistory and doing the rounds as advocated by Schiller:[14]

“You have to go the rounds from individual to individual in order to gather the totality of the race.”

In this way we can abandon and eschew amorphous ancestral veneration and get closer to restoring dignity. If we insist on invoking our ‘lived experience’ – we need to understand that self-affirmation and self-identification are completely incompatible with present-day Identitarian Politics: My racial composition and my position in the world are realities which I alone may determine… I do not expect to be told what I should consider myself to be. When it comes to grappling with the objective / subjective and rational / emotional aspects of historical research, I would suggest we look to our own home-grown Olive Schreiner and her two methods of portraying human life:[15]

“Human life may be painted according to two methods.

There is the stage method.

According to that each character is duly marshalled at first, and ticketed; we know with an immutable certainty that at the right crises each one will reappear and act his part, and, when the curtain falls, all will stand before it bowing. There is a sense of satisfaction in this, and of completeness.

But there is another method—the method of the life we all lead.

Here nothing can be prophesied. There is a strange coming and going of feet. Men appear, act and re-act upon each other, and pass away. When the crisis comes the man who would fit it does not return. When the curtain falls no one is ready. When the footlights are brightest they are blown out; and what the name of the play is no one knows. If there sits a spectator who knows, he sits so high that the players in the gaslight cannot hear his breathing.

Life may be painted according to either method; but the methods are different. The canons of criticism that bear upon the one cut cruelly upon the other.”

V Peculiarities of Cape slavery

Free yet still in chains …

The insightful comments concerning ‘assimilation versus apartheid’ by Hans F. Heese serve as a valuable starting point:[16]

“The question why some free-blacks, mestiços and castiços were assimilated into the white community while others were rejected during the 17th century and even later is a challenge for the researcher especially interested in social history. It is clear that rejection or assimilation were not necessarily connected. If inferences can be made on the basis of data from this seminar – which of necessity are openly based on a limited amount of documents and primary sources – it appears that the norm for acceptance in the white society was a lot more complicated than the simplistic Christian/Non-Christian or white/non-white dichotomy which is still generally posited. Evidently the person not born in slavery, had a better chance to be accepted into the economic and social life of whites, irrespective of biological descent. There were indeed many prominent free-burghers during the 17th and 18th centuries who were mestiços while some white castiços still found themselves in a state of slavery. The state of freedom or bondage of a person evidently contributed to his position in society. To equate the problems of identity of the 17th century with the colour problem of the 20th century, the following observation should suffice. It seems that white was sometimes black and black was sometimes white with a large grey area existing between the two poles. This grey area must still be investigated by the historian, anthropologist and political researcher and requires further research in the Netherlands, India, Portugal and Madagascar.”

The curious ‘disambiguation’ of the concept ‘Freedom’ from a Cape colonial context helps us to unravel the complexities surrounding the degrees of freedom and the degrees of bondage and the not unsimilar dehumanisation inextricably linked to both zielverkopers and lijfeijgen. And then there is the illusory and captivating term of slave itself :[17]

“These [the men] are themselves the laziest creatures that can be imagined, since their custom is to do nothing, or very little; and this is the life of the truly free Hottentots [Khoekhoe], the owners of the land as they call themselves, regarding us as the greatest slaves in the world with our so exactly fixed and precise way of life. If there is anything to be done, they let their women do it …”

We continue on that ‘long walk to freedom’ where a vrijbrief – letter of freedom acts as a chimera for subjects, burghers, citizens …

Khoikhoi and slavery

Slavery in South Africa was never ever an exclusively European or ‘white’ malpractice. Krotoa’s sister was a captive of war (Chainouqa / Cochoqua). The Gorachouqua feared enslavement by the Cochoqua and sought Dutch protection:[18]

“… This morning early the chiefs of the Gorachouquas arrived at the Fort, namely, Choro with his brother and 3 of their elders. They were escorted by one of our country guards, and brought with them 6 head of cattle as a present. They requested us to protect them against the Cochoquas or Saldanhars, who had yesterday again cut off their approaches to us and commenced to cause them great inconvenience, forcing them to permit them to search their houses, bags and packs, nominally in order to find tobacco, which they knew they did not possess. They were also already commencing to drive their cattle almost among their own, and suddenly and purposely drove off some last night. They had also been forbidden by them to retire to the Hout Bay or elsewhere, as Oedasoa having used up all the grass round about intended to keep those places for himself alone, without leaving any access to us to anyone. Already they had pitched their camps in such a manner as is their custom when they intend to harass anyone (te benauwen); so that they fear that the blow on their heads will be given them perhaps so soon as this evening or to-morrow, that they will be robbed of everything, and with wives and children made slaves of the Saldanhars.

They therefore prayed for our assistance & mediation, that this might be prevented, as they would as far as possible in return provide us with sufficient cattle, and that for the present one of the country guards may visit them every morning in order to enable them to call on the Commander daily under his protection. This was allowed them … In consequence these people felt as glad as if they had already been delivered from slavery.

A prisoner-of-war was offered to the Dutch as slave:[19]

The Soeswaas Captain Claas [Dorha alias Claas / Klaas (c. 1640-1701)] sent to inform us that he had killed 2 Gounema Hottentoos (our and his enemies), and at the same time presented us with a little boy about 10 years old, as a slave for the Company. He had spared him on account of his youth (onschuld), but the child was restored to him as his captive. It seems that these brutal Africans have commiseration for innocent childhood, which, however, is not considered by many Christian Potentates

What happened to the Hottentots?

Extinction? Genocide? Ethnocide? Self-effacement? Economically marginalized? Cultural vulnerability and incompatibility? There are no simple answers and attributing colonial animus is equally problematic …:

“To what extent did the VOC and the Dutch accommodate and integrate the aboriginal Khoe / San into colonial society? The converse must also be asked: to what extent did the Khoe / San accommodate and integrate the colonial Dutch into their non-colonial or inter-colonial world? To what extent were the Khoe / San peoples effaced; or put, differently: to what extent did these peoples efface themselves? [Jean O’Brien argues that Native Americans have been rendered invisible because they aided and abetted their paleface invaders thereby constructing the myth of ‘Indian’ extinction [Dispossession by degrees: Indian Land & Identity in Natick, 1650-1790]. Micro-historical and genealogical research and re-evaluation of extant records and recorded individuals – Historians often neglect to identify individually the characters in their drama and to contextualise them as a means of countering questionable generalisations about human behaviour – including women – from the earliest period of regular contact, collision and relations – The reductionist categories are derived from Urs Bitterli, Cultures in Conflict: Encounters Between European and Non-European Cultures, 1492-1800 (translated by Ritchie Robertson, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California 1989)] – help to provide answers to these questions. Unhelpful in this regard are absolute and unsubstantiated statements such as that by Dr Con G. de Wet in his chapter on the social and cultural life of the Cape’s free burgher population: …in die oorspronklike bronne is daar geen [sic] bewyse gevind van gewone sosiale verkeer tussen vryliede en Hottentotte nie” [20]…

“The real Hottentot is extinct, I believe, in the Colony; what one now sees are all ‘Bastaards’, the Dutch name for their own descendants by Hottentot women. These mongrel Hottentots, who do all the work, are an affliction to behold—debased and shrivelled with drink, and drunk all day long; sullen wretched creatures—so unlike the bright Malays and cheery pleasant blacks and browns of Capetown, who never pass you without a kind word and sunny smile or broad African grin, selon their colour and shape of face. I look back fondly to the gracious soft-looking Malagasse woman who used to give me a chair under the big tree near Rathfelders, and a cup of ‘bosjesthée’ (herb tea), and talk so prettily in her soft voice;—it is such a contrast to these poor animals, who glower at one quite unpleasantly. All the hovels I was in at Capetown were very fairly clean, and I went into numbers. They almost all contained a handsome bed, with, at least, eight pillows. If you only look at the door with a friendly glance, you are implored to come in and sit down, and usually offered a ‘coppj’ (cup) of herb tea, which they are quite grateful to one for drinking. I never saw or heard a hint of ‘backsheesh’, nor did I ever give it, on principle and I was always recognised and invited to come again with the greatest eagerness. ‘An indulgence of talk’ from an English ‘Missis’ seemed the height of gratification, and the pride and pleasure of giving hospitality a sufficient reward. But here it is quite different. I suppose the benefits of the emancipation were felt at Capetown sooner than in the country, and the Malay population there furnishes a strong element of sobriety and respectability, which sets an example to the other coloured people. Harvest is now going on, and the so-called Hottentots are earning 2s. 6d. a day, with rations and wine. But all the money goes at the ‘canteen’ in drink, and the poor wretched men and women look wasted and degraded. The children are pretty, and a few of them are half-breed girls, who do very well, unless a white man admires them; and then they think it quite an honour to have a whitey-brown child, which happens at about fifteen, by which age they look full twenty. Lady Duff Gordon, LETTER IV JOURNEY TO CALEDON – Caledon, Dec. 10th. [1864]

American historian Richard Elphick’s cautious multi-causal, open-ended – but constraining much ado about nothing – assessment of our own initial cultural close-encounters-of-a-first-kind in his Khoikhoi and the founding of White South Africa,is worthy of revisionist scrutiny:[21]

“Thus, the leading features of Khoikhoi decline were the complex interconnections of its many causes, and the predominance of broad processes over discrete episodes of diplomacy and conquest. For these reasons Khoikhoi decline was a mystery both to the Europeans who initiated it and to nineteenth-century investigators who vainly sought to explain it by a single cause, be it genocide or plague. For these reasons, too, the story has hardly ever been told in recent times; it has few villains, fewer heroes, and little of the drama that attracts novelists and historians to later phases of settler-native conflict in southern Africa. Yet the process of Khoikhoi decline should be understood, and not only because brown and white South Africans still live with its consequences today. For it is a fact worth pondering that the European subjugation of southern Africa began, not because statesmen or merchants willed it, nor because abstract forces of history made it necessary; but because thousands of ordinary men [sic], white and brown, quietly pursued their goals, unaware of their fateful consequences.”

Slave Master’s Status determines slave’s future place in colonial society

Trajectories of Slaves’ lives invariably diversify depending on the status of their owners:

- VOC officials

- patrician families

- free-burghers

- free-blacks

- political exiles [Jonker rebellion, Tambora and Late Muslim arrivals; Lady Duff Gordon & Genadendal]

Peculiarities Specified

- Slavery is abolished in Europe (including Netherlands) but resurrected partially after voyages of ‘Discovery’

- Asian Caste systems (also Jews and Gypsies in Europe and bestiality), Hindu practice of burning widows alive and Guinean human (female virgin) sacrifices need to be brought into the equation when contextualizing slavery at the Cape of Good Hope.

- ‘Colonial Slavery’ was a LEGAL institution

- Khoe were never formally enslaved – Krotoa as a ‘slave’ (presentist) – in contradistinction to Dutch East India

- Baptism of slaves – Synod of Dort

- distinctive from Trans-Atlantic and Arab slavery – plantations / castration / religious conversion / language (cf English in USA and Afrikaans in SA)

- Ethnic breakdown – Malagasy and Masbiekers eventually outnumber the Asian (Indian, Sri Lankan / Indonesian / Malaysian) slaves – this has implications re the make-up of the ‘Coloured’ communities

- Clothing restrictions (shoes, hats and luxury items)

- Minnamoers – fons et origo of the Afrikaans language [?] – unlike US or Canada [?]

- Nonya & Nyai – ‘rape’

Slave women – even once freed (are made to) take on role of domestic servant-cum-concubine-cum-nursemaid in ‘Cape Dutch’ colonial households. Triple role mirrors position(ing) of njai and nyonya in SE Asia. Terms (derived from Indonesian languages & Portuguese, respectively) become fully integrated in both Cape Dutch dialect Kaaps and what is today institutionalised as Afrikaans as a term of respect for not only white women, but also mixed race women of a higher social standing: nonnie. It has also left us with the more vulgar term naai for ‘fornication’ when debasing human sexual intercourse by equating it with the ‘mating’ of animals.

Njai / njaie / nyai / nyaie / nyahi / nyi = term for women kept as ‘housekeepers’, ‘companions’, and ‘concubines’ in Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia) and evidently also at the Cape. Position of njai – always subservient, being the man’s housekeeper and companion, before she is his concubine. In the Javanese and Balinese languages, the word nyai means ‘sister’. In Sundanese the term nyai refers to ‘miss’ or young woman, while in Betawi dialect, nyai refers to ‘grandmother’ or elderly lady. The Great Dictionary of the Indonesian Language of the Language Centre gives three definitions for njai: as a term for referring to a married or unmarried woman, as a term for referring to a woman older than the speaker, and for the concubine of a non-Indonesian. This last definition gains traction in the 17th century when Balinese njais first become common in the colonial capital of Batavia (now Jakarta). The word is sometimes simply translated as ‘mistress’. A variety of other terms are also used to refer to the njai, with varying degrees of positive and negative connotations. In the 19th century the term inlandse huishoudster, or simply huishoudster (‘housekeeper’), is common. The njai are also known as moentji, from the Dutch diminutive mondje, meaning ‘mouth’, and the more negative snaar (‘strings’); both refer to the njai’s verbal / oral propensities. As the njai can also serve as a translator and language teacher, substitute terms such as boek (‘book’) and woordenbooek (‘dictionary’) also abound. Objectification of the njai is found in terms such as meubel (‘furniture’) and inventarisstuk (‘inventory piece’).

Nyonya (also spelled nyonyah / nonya) / nonje / nonna / nonnie) = Malay, Indonesian and Cape Dutch / Kaaps / Afrikaans honorifics and (ostensibly diminutive) terms of affection used to refer to a ‘foreign married lady’ – but at the Cape also as term of respect for older women freed from slavery. Loan word, borrowed from old Portuguese word for lady donha / dona (compare, for instance, Macanese creole nhonha spoken on Macau – a Portuguese colony for 464 years). Malays addressed foreign women (and those appearing foreign) as nyonya using that term for Straits-Chinese women as well. It gradually became more exclusively associated with them. In Penang Hokkien, it is pronounced nō͘-niâ (in Pe̍h-ōe-jī), and sometimes written with the phonetic loan characters 娘惹.

- plight of male slaves

- concubinage / marriage [Jannetje Bort versus Kaet; (Jan Groff; Maria da Costa & Maaij Ansela & Catharina van Malabar]

1660: Barent Waendersz: van Varich / Varick

… vryman alhier aan gemelte Caap … Heeft yemant van u volck met de slavinnen te doen gehadt, ende met kint gemaeckt? … segt het vrij, daer is niet aengelegen, het is ten dienste van de Compagnie.

“Declaration of Arent Gerritsz: van der Elburgh, sailor, and Adriaan Bastiaansz: Peereboom, marine, made at the request of Barend Waendersz:, of Varick, freeman here, that Theunis Frederiksz:, of Weserysen, sailor, had publicly said, whilst standing before the gate of the horn works, that the Commander Jan van Riebeeck had come to the Bosheuvel and said to Barend Waendersz:, who lives there: “Has any of your men had anything to do with the female slaves and fructified them?” and that Barend answered, “No, sir.” That Riebeeck replied: “Barend, did you have anything to do in the matter? Tell it freely, no harm is done, it is for the benefit of the Company. Barend replied: “Yes, sir.” Riebeeck answered: “Then go to the fiscal and settle the matter, no harm is done (it is not of any importance). The above confirmed by oath.”

Jan Groff

Cherchez les femmes! Grof’s earlier brief encounter, liaison or concubinage (… het schandelyke crime van fornicatie ofte hoerendom) with the commander’s private slave woman appears not to blemish his standing in Cape colonial society – on the contrary, it may have enhanced it. However, his later unashamed, indiscrete, defiant and public long‐term but illegal concubinage with his own slave appears to have had the opposite effect on him, his slave and her offspring. Ironically, his illegitimate daughter (Susanna) became mistress of the not insubstantial Spier estate at Stellenbosch

- conditional freedom – sold back into slavery and inheritance [Schoeman / Newton-King – both incline to ‘equality’ on par with ‘White’ burgher population once freed]

- wealth accumulation while in bondage

- Substituting slaves for manumission (introduced later as preventative measure to control increasing poverty amongst free-black population)

- slave contact with Batavia – Maaij Claesje, Maria da Costa and Maria Domingo

- slaves taken to Patria and automatic freedom – Maria Stuart / Claas Jonas

- cruelty towards slave – Tido / Michiel Otto and Andries Otto / Opperman / Botha

- special treatment – Maaij Ansela and Jannetje Bort

- ex-Slaves owning slaves – Maaij Ansela and Zwarte Maria

- success despite adversity – Cairns / Schoeman / Hislop – family networks – ‘dynasties’

- Company slave versus private slave – access to education (important alternative to wealth in ‘dynasty’ formation)

- Access to education (eg Jonker and Snijman) (cf. comment by Sculley re access to education – Hendrik Caesars vs Saartje Baartman) (Africano)

- better life than before (caste system and indigenous slavery and burning widows)

- eene moeder maakt geen bastaard (but exception of adultery / incest who can never be legitimized) – Dutch law of inheritance

VI Cape Slave ‘Dynasties’, Family Networks and colonial elites

Gerald Groenewald (UJ) ‘Dynasty building, family networks and social capital: Alcohol pachters and the development of a colonial elite at the Cape of Good Hope, c. 1760-1790 – Eksteen and Heyns and their dealings with slave families are insufficiently explored.

The Commanders’ Slaves

1 indigenous Khoe and 15 imported slave women (4 Indian, 2 Arab, 3 West African and 3 Angolan) initially serve in household of Jan van Riebeeck, Cape’s 1st VOC commander (1652-1662)

- Krotoa aka Eva Meerhoff (c. 1643-1674) – descendants include Jan Smuts, Paul Kruger and a huge swathe of ‘White’ South Africans

- Koddo aka Cornelia van Abissina – descendants include Slave Lodge matron, Armozijn Claes:, mission-helper, Machtelt Schmidt, Paul Kruger, and Heyns, Jonas, Combrink families; the mixed race Eksteen and Oberholster pioneers on the frontier and also the notorious the frontiersman, Willem Namaqua also Coloured man and Voortrekker secretary JG Bantjes (1817-1877)

- Sabba aka Lijsbeth van Abissina – descendants include Louis Botha, intrepid frontiersman, Coenraad de Buys, Buys Basters, and major branches of Coetzee and Pretorius families

- Hoena aka Anna van Guinea – descendants include Colyn family – owners of portions of Constantia as well as Campher and Oelofse families

- Gegeima / Jajenne aka Lobbetje – descendants include the Van der Schyff family

- Maria van Guinea – her only daughter appears to have died childless

- Maaij Claesje Jansz: van Angola (1652-1732) – descendants include Hartog and Hagendoorn families

The transoceanic lives of this remarkable, radical, and resilient slave woman, Maaij Claesje Jansz: van Angola (1652-1732), has escaped the notice of historians and researchers. An Angolan waif (aged 6) forcefully enslaved by fellow Black Africans, she is removed across the Atlantic Ocean by their Portuguese clients from her African homeland, and again taken (1658) – this time by the Dutch as prize off the Brazilian coast of Bahia – and returned across the Atlantic Ocean on the ship Amersfoort to Africa – but further south – and dumped at the Cape of Good Hope. Sold by the Dutch East India Company (VOC), she becomes a private slave in the household of the colony’s 1st commander, Jan van Riebeeck. Thereafter she is sold to the colony’s secunde, the bachelor Roelof de Man; again resold to the Company; sold again as a private slave to the married Lieutenant Abraham Schut; and thereafter to the colony’s 4th commander, the unmarried Jacob Borghorst; before being again sold back to the Company. Taken across the Indian Ocean as a Company slave on loan to Indonesia (1689) in attendance to a senior VOC official’s wife, she returns from Batavia across the Indian Ocean to the Cape to claim her freedom promised her. She is accordingly manumitted but soon re-employed as the free-midwife (frij froemoeder) to the Company’s Slave Lodge. She has several children – mostly fathered by prominent European officials and/or free-burghers. At least one of her granddaughters, occupies the pivotal position of school mistress (school matres in s’ Comp[agnie]s Slaven Quartier) in the Company Slave Lodge (in 1685 & 1689 respectively). Claesje dies (1732) – at the ripe old age of 80 – having lived at the Cape of Good Hope (and briefly in Batavia) for 74 years.

- Christina (Christijn) van Angola – descendants include Van Biljon, Huijtema and Bakker families

- Francina (Francijn) van Angola – descendants in Company Slave Lodge

- Maaij Isabella van Angola – descendants include the Beyers and Esterhuizen families

- Maria van Angola – descendants include Steyn and Romond families

- Maria Pekenijn van Angola – Jacobs and Stolts descendants end up as pioneers on the frontier and amongst Hottentot Corps; another descendant is the Coloured man and Voortrekker secretary JG Bantjes (1817-1877)

- Catharina van Paliacatta aka Groote Catrijn (c. 1631-1683) – descendants include the Snyman and Botha families

- Maaij Angela / Ansela / Ansiela / Engela van Bengale aka Moeder Jagt (dies 1720) – descendants end up as part of ruling colonial elite throughout Dutch and British empires: Jan Smuts, Maria Koopmans-de Wet, Gysbert Hemmy

- Dominga van Bengale

- Maria da Costa van Bengale / Paliacatta – descendants find themselves amongst colonial and Slave Lodge elite

Different Fates / Different Outcomes – Maaij Ansela versus Maria da Costa versus Catharina van Malabar versus Sabba / Koddo

A Changing racial, ethnic, cultural, religious landscape

- Vrij Corps – a new sub-group

- 1713 Small Pox Epidemic – free-black and Khoi greatly diminished

- ‘New’ Christian and Muslim ‘Coloured’ Community (Lady Duff)

Thankful for the waters of the Modder River? Separate but Equal – Verwey vs Basson

The legacy of Jan van Riebeeck’s slave women is one of the unexpected and un-Woke outcomes of South Africa’s unique colonial legacy. The lesser-known aspects of conquest, indigeneity, colonization and decolonization – often contradicting newly imposed Political (mis)Correctness and likely again to be silenced – has induced a situation whereby a great many – if not most – South Africans classified ‘White’ and ‘Cape Coloured’ under apartheid happen to actually be direct descendants of both indigenous African and Africasian slave women. Many descendants end up, not only as ‘colonisers’, colonial officials and slave owners in their own right, but also as founders of nomadic mixed race clans such as the Griqua, Koranna, Nama, Oorlam, and the Buys, Cloete, Van Wyk, and Rehoboth Basters …

Denial or Affirmation? Blend is Beautiful

The reality of shared indigenous and slave roots across a diminishing racial or ethnic divide, however, cannot any longer be denied or suppressed.

There is, however, an increasingly disturbing ideological pull, however, towards Diversity. The outcome, it must be stressed, is seldom inclusivity. Rather, it tends towards dissent and exclusivity … [Lessons of HHH school debate (1976) – Will the two language groups ever come together?]

So, “Good-bye rainbow nation!”and “Good-bye colour-blind wishful thinking!”

Published Sources

- Con G. de Wet, Die Vryliede en Vryswartes in die Kaapse Nedersetting 1657-1707 (Historiese Publikasie Vereniging, Kaapstad 1981)

- Urs Bitterli, Cultures in Conflict: Encounters Between European and Non-European Cultures, 1492-1800 (translated by Ritchie Robertson, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California 1989).

- Ran Greenstein, ‘Settler Societies and Political Conflict: A Comparative Historical Study of South Africa and Israel’ (28 October 1990)

- Gerald Groenewald, ‘Dynasty building, family networks and social capital: Alcohol pachters and the development of a colonial elite at the Cape of Good Hope, c. 1760-1790’ (Department of Historical Studies University of Johannesburg)

- Dr Hans F. Heese (‘Identiteitsprobleme gedurende die 17de eeu’, Kronos, vol. 1 (1979)

- Hans F. Heese, Groep Sonder Grense: Die Rol en Status van die Gemengde Bevolking aan die Kaap, 1652-1795)

- Hans F. Heese, ‘The Dutch-Afrikaner Genealogical and Cultural Heritage’, Paper presented to the GSSA (Western Cape Branch) meeting held at the Genealogical Institute of S.A. (GISA), Stellenbosch 8 August 1998.

- Hans Friedrich Heese (Research Fellow, Department of History, University of Stellenbosch, South Africa), ‘Cape of Good Hope? Meeting Place of Unwilling Migrants from Africa, Asia and Indigenous People’, Insights of Anthropology, vol. 4, Issue 1 (2020), pp. 268-279

- Jean O’Brien, Dispossession by degrees: Indian Land & Identity in Natick, 1650-1790

- Robert C.-H. Shell (University of the Western Cape), ‘Immigration – the forgotten factor in Cape colonial Frontier expansion, 1658 to 18171’, Safundi, Journal of South African And American Comparative Studies, no. 18 (April 2005)

- Nigel Worden (2007) ‘New Approaches to VOC History in South Africa’, South African Historical Journal, 59:1, 3-18 (2017)

[1] Gysbert Hemmy (1746-1798), Preface – An Inaugural Juridical Dissertation Concerning the Testimony of Æthiopians, Chinese and Other Pagans in – the East Indies (Leiden, 7 September 1770) [translated from the Latin]. Hemmy is the great-great-grandson of Cape of Good Hope’s 1st VOC commander Jan van Riebeeck, Maaij Ansela van Bengale (died 1720).

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_in_Bugis_society

[3] https://mansellupham.wordpress.com/2020/02/10/boniface-permission-to-stay/

[4] Christoffel Coetzee de Villiers & Cornelis Pama, Genealogies of Old South African Families, A.A. Balkema, Cape Town 1966.

[5] Aptly coined by William Mansell Upham (1927-2006)

[6] Elizabeth Helen Ludlow, Missions and Emancipation in the South Western Cape: A Case Study of Groenekloof (Mamre), 1838-1852 (Unpublished Masters Dissertation, UCT) and Kerry Ward [in Worden, Nigel & Crais, Clifton (eds.): Breaking the Chains: Slavery and its Legacy in the Nineteenth-Century Cape Colony (Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg 1994).

[7] Mansell G. Upham, Brotherly Love at Philadelphia – https://mansellupham.wordpress.com/2019/06/15/brotherly-love-at-philadelphia-the-widow-priem-the-alternative-brakfontein-congregation/

[8] Cf. Hans Heese’s preference for the term ‘brown people’ instead of the previously colonially and apartheid category.ized ‘Cape Coloured’ population: “The paper mainly deals with the large number of slaves from Asia and Africa imported to the Cape of Good Hope during the period 1658-1807. Apart from the (in-)human treatment of people from different continents, and the evils of slavery as a system, the new migrants eventually fused with the indigenous Khoikhoi, San and European population to create a new group of people that would eventually become known as the “Cape Coloured” community (In Afrikaans “kleurlinge” or “bruin mense”). At present this group consists of nearly 5 million people; 10% of the total South African population.”

[9] https://mansellupham.wordpress.com/2020/12/20/camissa-kamma-river-kammasa-truth-kamma-ostensible/

[10] https://mansellupham.wordpress.com/2021/10/25/zwarte-maria-everts-former-slave-turned-slave-owner-verbatim-transcription-of-her-last-will-testament-1713/

[11] https://mansellupham.wordpress.com/2019/08/15/when-we-dead-awaken-resurrecting-recollecting-restraining-patenting-labelling-bottling-putting-the-lid-on-ancestors/

[12] Robert Tombs, ‘Wokeness and the collapse of intellectual freedom in the West’, The Spectator (28 August 2021).

[13] cf. https://mansellupham.wordpress.com/2019/11/17/creolisation-indigenisation-burlamacchi-diodati-family-ties-in-the-dutch-voc-empire/

[14] Friedrich Schiller (2012), On the Aesthetic Education of Man in a Series of Letters (Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen in einer Reihe von Briefen), 1794).

[15] Olive Schreiner

[16] These I have translated from the Afrikaans – see Hans F. Heese, ‘Identiteitsprobleme gedurende die 17de eeu’, Kronos,vol. 1 (1979), p. 33)

[17] François Valentijn (1666-1727), Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën [`Old and New East-India`] (1726).

[18] Précis: Riebeeck’s Journal (30 November 1661), vol. III, pp. 311-313.

[19] Journal (27 September 1673).

[20] Die Vryliede en Vryswartes in die Kaapse Nedersetting 1657-1707 (Historiese Publikasie Vereniging, Kaapstad 1981), p. 128.

[21] https://mansellupham.wordpress.com/2020/03/31/the-kutykum-factor-or-tit-for-tat-under-western-eyes-and-southern-skies-occidental-accidents-of-history/