ZARA

(c. 1648-1671)

by Mansell George Upham ©

An inquiry into the (mis)application of traditionally prescribed punishment against persons committing suicide during the VOC’s colonial occupation of the Cape of Good Hope

This article amplifies, contextualizes and re-evaluates the life of the Cape aboriginal woman called ZARA alias SARA (c. 1648-1671). Preserved original records and published sources have been closely scrutinized. This follows a preliminary inquiry into the judicial treatment of the sin and crime of suicide during the VOC’s colonial occupation of the Cape. Zara’s extraordinary case is contrasted with other recorded incidents of suicide at the Cape. Zara’s corpse was not only put on trial, but also impaled and left to rot in public. Significantly, all the other cases of suicide considered here, generally were handled by the Cape’s colonial administration contrary to the traditional and prescribed punishment for suicides: impalement and the denial of burial in consecrated ground.

On 18 December 1671 the suspended corpse of the 24-year-old female Hottentot suicide Zara (also found as Sara) was found hanging in the sheep pen of the freed slave woman Angela van Bengale (alias Maaij Ansela), wife of the free-burgher Arnoldus Willemsz: Basson from Wesel (alias Jagt).[1] She had been found by Maaij Ansela and François Champelier (from Ghent). Although the Cape’s deceased commander, Pieter Hackius, had barely been put to rest on 3 December 1671, a ‘provisional administration’under Daniel Froymanteau (from Leiden) had quickly been put in place. A much-reduced Council of Justice was quick to convene the same day the corpse had been discovered:

The Council having examined two persons namely Francois Champelaar, servant of Joris Jans:, and Angela of Bengal, wife of Arnoldus Willems:, who state that the said Hottentot was found hanging in her own gown band, fastened in the thatch overhead; and that on their first coming, they observed some motion in the veins of the neck, which induced said Champelaar to cut down the body in hopes that life was not extinct; but that, on the body falling to the ground, it was found that Satan had already taken possession of her brutal soul.

The Company Journal entry for that day states that:

This morning, very early, it came to our ears that a certain Hottentoo girl, about 24 years old, who had, since her early childhood been respectably educated here by civilised burghers, carefully taught the Dutch language, and trained in burgher manners, had, without our being able to discover any reason, hanged herself in the sheep pen of a certain burgher by means of her cabaij band. An inquest was held on the body by the Fiscal in presence of Commissioners, but no wounds were found on the body, so that she died from suffocation … According to resolution of the Council, the body of the female Hottentoo was towards evening dragged by the donkey to the gallows, and there, as a loathing of such abominableness, placed with the head in a fork, and hanged between Heaven and earth, as will be seen in the Criminal Roll.

Less than a month later, Zara’s impalement had been interrupted. On Sunday 10 January 1672 the Company Journal – also revealing that Dutch-Aborigine relations were at an all-time low – noted the following:

Discovered this morning that the fork on which the female Hottentoo had been hanged had been taken down and fallen over. Careful inquiry failed to discover the author. During the afternoon the mounted guard brought in five wanton Hottentoos tied to one another with ropes and charged … The day of the Lord religiously kept.

Zara’s subsequent ‘resurrection’ was noted in the Company Journal of 11 January 1672:

Towards evening, in order to carry out the sentence, the above-mentioned female Hottentoo was again lifted on the fork.

Zara appears to be the Cape’s first recorded suicide. More than 70 years later, Zara was still the only recorded suicide at the Cape to have her corpse dishonoured in terms of European traditional, juridical and judicially prescribed punishment. That ‘temporary insanity’ came to be invoked in ensuing incidents – especially in the case of non-indigenous suicides at the Cape – begs further inquiry …

European attitudes towards Suicide

Suicides were formerly buried ignominiously on the high-road, with a stake thrust through their body, and without Christian rites

Chamber: Encyclopædia, 1x. p. 184, col. 1

Janet Todd summarizes both the traditional and changing European attitudes towards suicide:[2]

Christianity had made suicide a sin by calling it self-murder. The corpse of a suicide was supposed to be buried with a stake on the public highway. The state in its turn had made the act criminal and sought to confiscate the criminal-victim’s property and money. In England suicide remained both sin and crime throughout the eighteenth century – staking and burying on the highway officially stopped in 1823, forfeiture only in 1870 – but the attitudes were modified long before. By the last decades of the eighteenth century, penalties were almost always avoided, even in the clearest of cases … Although suicide still excited horror and demanded burial in unconsecrated ground, a secular attitude was gaining strength. Along the Thames and by the Serpentine, humanitarian groups set up suicide stations to resuscitate the living or identify the dead … Socio-historical studies always consider gender in suicide. While men chose to hang or shoot themselves, women overwhelmingly chose drowning or poison, a slower method leaving the body intact.

Todd, also gives a useful literary and philosophical overview:

For the literary classes two new attitudes were available, the rational and the romantic. The philosopher David Hume regarded suicide as a native liberty, and asked why we think that a ‘man who tired of life, and hunted by pain and misery, bravely overcomes all the natural terrors of death … has incurred the indignation of his Creator. When pain and sickness, shame and poverty in any combination are overwhelming, when a person has weighed up the benefits of the future against the misery of the present, then he has a right to proceed to end his being and not consider either God or society since he is not obliged to do a small good to others at the expense of a great harm to himself … Godwin sought to refine Hume. In the first version of Political Justice he saw suicide as neither criminal nor sinful, but he distrusted the Humean motives for escape from life – pain and shame – for pain, he claimed, was momentary and disgrace imaginary. In a later edition he became more utilitarian, insisting that the would-be suicide consider the net pain caused by life or suicide, including in the latter case the misery to remaining relatives.

European suicides at the Cape

… a mournful and melancholy spirit … always fe[eling] aggrieved by all worldy matters however trivial …

Europeans at the Cape who are on record for committing suicide, vary from two soldiers, two free-burghers, a minister of the church and a high-ranking member of the Council of Policy. Significantly, unlike Zara, not one of these suicides were ever ‘punished’ post mortem in the juridically and judicially prescribed manner for hating their lives and for purposes of deterrence to others.

On 17 May 1673 the Council of Justice deliberated on the question of suicide in the case of Jan Elias Busch. Rather than apply the prescribed punishment for suicide, the council opted instead to rationalize the suicide as a case of ‘temporary insanity’:[3]

… When the gate was opened this morning the sergeant of the New Castle reported that last night the soldier Jan Elias Busch of Dorlach had cut his throat and died. At once Commissioners and the Fiscal were deputed to investigate the matter and examine such witnesses as might be able to give information. They reported that the soldier had cut his throat, and that from the evidence of the witnesses it appeared that feeling somewhat indisposed last night he had taken some medicine to open his bowels; that about 3 in the morning he had said to one of the witnesses that he was going outside the barracks to get a little fresh air; and that shortly afterwards deponent having been sent out with some others to look for him, had found him lying outside the curtain of the Fort on the sea shore bathed in blood, with a bloody knife at his side. During the evening meeting the question was discussed whether the suicide should be allowed burial, or whether the Council should proceed according to law with the corpse. It was decided to bury it, as it was presumed that the patient, in consequence of his indisposition, must have suffered from temporary insanity, and did not commit the act because he hated his life, but that he had been bereft of his senses and thus killed himself. In such a case the strictness of the law is not desired, which decrees that such malefactor shall be dealt with as an example to others …

On Friday evening of 28 September 1703 Abraham Bastiaansz: Pyl (married to Cornelia Cornelissen, the daughter of Cornelis Claesz: (from Utrecht) aka Kees de Boer and Catharina van Malabar), was brought soaking wet into the house of the free-black Jan Luij / Leeuw van Ceylon by the latter’s children who had rescued him out of the Eerste River. Pyl who was made to sit and dry himself that evening before the fire on the understanding that he would spend the night there. Later that night gurgling and screams rudely awakened the family. Pyl was found lying facewards on the ground with his throat slit by a knife. The landdrost Pieter Robberts: and two heemraden Dirk Coetse [Coetzee] and Guilliam du Toit were duly called. On their arrival they found Pyl still alive. His throat had been cut through zoodanig dat de longe-pijp geheel afgesneden was. On asking Pyl what had happened, he had indicated that the wound had been self-inflicted. But after the surgeon Jean Prieur du Plessis had dressed the wound, Pyl could be more clearly heard to confirm two or three times that he had indeed slit his own throat. When asked why he answered simply, and without any further explanation: Mijn vrouw is er de oorsaak van … He died a few days later.[4] His widow soon shacked up with a Dane named Richard Adolphus Rigt (from Tønder).

In 1704 the minister Hercules van Loon committed suicide. His suicide, an embarrassment in the extreme, was covered up to avoid any scandal. Were it not for the writings of Peter Kolb(e), this incident may well have been successfully suppressed:[5]

Sy uiteinde is dan ook tragies. Onderwyl hy op 26.6.1704 van sy plaas Hercules’ Pilaar by Joostenburg te perd op pad is na Stellenbosch, het hy, volgens Peter Kolbe, in die eensame veld ‘zich zelven met een pennemes den hals afgsneden, zonder dat iemand ooyt heeft geweten, waar door hy tot die wanhoop vervallen is.’

In 1705 Hendrik Munkerus took his own life:[6]

The morning curtains opened themselves today with a sorrowful and miserable occurrence connected with the person of the junior merchant and cashier Henricus Munkerus, who was found dead about eight o’clock in his bedroom, before his bed (his wife being in the Tiger Bergen on her farm). He lay in his underclothing with a Japanese cloak around his body, having fallen forward with his face to the earth. His whole skull, as far as above the nose, was found shot away with a pistol and smashed. The brains were scattered about the room. After the proper inspection had taken place in the presence of the Fiscal and Commissioners, attempts were made by the former to obtain information concerning this horrible affair, but he could gain nothing more from the domestics than that the said Munkerus having arrived home healthy and well the preceding night at 9 o’clock, went into his room shortly afterwards in order to go to bed, closing the door behind him. That not being accustomed to his lying in bed so late, they had at the time mentioned opened the door, and entering, found the body as described. At once they had given notice to the Fiscal. They also stated that they had heard no report or the least noise, and as the windows were carefully locked on the outside and inside, it was taken for granted that he had killed himself in this horrible manner. This was confirmed by the presence of a discharged pistol near the body, a small powder horn filled with powder on a chair before the bed and three pistol bullets found in his pockets.

Later, disgruntled freemen at the Cape were to blame the besieged governor, Willem Adriaan van der Stel, for his death. Van der Stel denied this accusation:[7]

The Governor replies that no more wicked and libellous lie could be invented than that he had brought the cashier Munkerus to that state of despair in which he killed himself as the result of persecutions and oppression, for he can conscientiously declare that he had never given him cause for such unnatural thought, and never treated him badly; but the general presumptions were that this reasonless man had always suffered from a mournful and melancholy spirit, and always felt aggrieved by all worldy matters however trivial they were, and that finally he came to this desperate resolve.

On 26 September 1716, the body of a soldier Coert Simonsz: Bruyningh who had committed suicide literally fell into view and despite the suicide’s negligence, became a source of merriment:[8]

The thoughtfulness of the soldier Coert Simonsz: Bruyningh went so far that he hanged himself in the belfry of the tower from a beam under the bell, and this might have caused the death of another man, viz the rondganger (the man who makes the rounds) and whose turn was to strike 4 o’clock. For that purpose he mounted the ladder, but an arm of the hangebast (gallows bird) struck him in the face. This unexpected encounter so startled him that he fell down in a swoon, right from the top to the bottom. The officer of the guard, astonished why the hour had not been struck, sent a man to enquire the reason, when, it was found that the rondganger who had to strike the hour, was lying down half-dead in consequence of his unexpected contact with the suicide. He soon, however, came to himself again, and about 7 p.m. the dead body fell through the noose.

In 1743 the French-speaking refugee (Huguenot) Jacques Nourthier [Northier] committed suicide. He appears not to have been punished post mortem for having done so.[9]

Suicide amongst the slaves

During the period researched, no direct references or trials of any slave suicides have come to light.[10] Suicide amongst the slaves at the Cape thereafter, appears to have been frequent. The ‘practice’ appears to have been particular prevalent amongst Malagasy slaves.[11]

Suicide at the Cape, as in other slave societies, was the most tragic form of slave response, reflecting the desperation of the slave condition.[12] Nigel Worden warns us, however, that distinctions must be made in the nature and the possible motivations of slave suicide. Bids to avoid the torture of certain painful death by the authorities when slaves were on the point of capture after committing crimes or running away are less indicative of the desperation of some slaves. Desperation is more acute in suicide cases that are planned as a means of escaping from the ordinary situation of the slave not being threatened by imminent punishment.

Suicide amongst the aborigines

The extent that suicide occurred amongst the Cape’s aboriginal population is not really known. We do, however, have an inkling of sorts, thanks to the writing of Dapper:[13]

As instances of true mutual love among these savages, we may mention two remarkable episodes which happened there a few years ago. In the one a widow, through sadness and grief at the loss of her husband, sprang into a pit full of wood which had been set alight, and burned herself to death. In the other, a young girl, rendered disconsolate because her parents had severely whipped her lover on finding that he had slept with her against their will, threw herself down from a rock and was smashed to pieces.

Zara and the Lacus Household

… in the room behind, Rebekah slept with Sartje – a little, yellow-brown, frizzly-haired girl she had adopted five years before as a little baby and treated in all ways as her own child, except that it was taught to call her mistress.

Olive Schreiner (24 March 1855 – 11 December 1920), Fireflies in the Dark, From Man to Man – or perhaps only …

Zara, ostensibly a ‘detribalised’ Hottentot like her mother, was placed at a young age into the service of the secunde Hendrik Lacus (from Wesel in the Duchy of Cleves) and his wife, Lydia de Pape.[14] The use of local aborigine girls as house servants to VOC officials and free-burghers was an established practice at the Cape. Thus the indigenes Krotoa (alias Eva Meerhoff) and Cornelia, Dobbeltje and Vogelstruys came to be part of the Van Riebeeck household:[15]

… The GORINGHAICONAS, of whom Herry has been usually called the Captain; these are strandloopers, or fishers, who are, exclusive of women and children, not above 18 men in number, supporting themselves, without the least live stock of any description, by fishing from the rocks along the coast, thus furnishing a great accommodation to the Company’s people and freemen, and also rendering much assistance to those who keep house, by washing, scouring, fetching firewood, and other domestic work; and some of them placing their little daughters in the service of the married people, where they are clothed in our manner, but they must have a slack rein, and will not be kept strictly, such appears to be contrary to their nature; some of the, however begin to be tolerably civilized, and the Dutch language is so far implanted among them, old and young, that nothing can any longer be kept secret when mentioned in their presence …

The indigenes living close to the fort were initially a motley throng of detribalised Quena known as the Goringhaicona (Watermans) and an apparent offshoot of the Goringhaiqua (Caepmans):[16]

The Goringhaiconas subsist in a great measure by begging and stealing. – Among this ugly Hottentoo race, there is yet another sort called Goringhaicona, whose chief or captain, named Herry, has been dead for the last three years; these we have daily in our sight and about our ears, within and without the fort, as they possess no cattle whatever, but are strandloopers, living by fishing from the rocks. They were at first, on my arrival [1662], not more than 30 in number, but they have since procured some addition to their numbers from similar rabble out of the interior, and they now constitute a gang, including women and children, of 70, 80, or more. They make shift for themselves by night close by, in little hovels in the sand hills; in the day time, however, you may see some of the sluggard (luyaerts) helping to scour, wash, chop wood, fetch water, or herd sheep for our burgers, or boiling a pot of rice for some of the soldiers; but they will never set hand to any work, or put one foot before the other, until you have promised to give them a good quantity of tobacco or food, or drink. Others of the lazy crew, (who are much worse still, and are not to be induced to perform any work whatever,) live by begging, or seek a subsistence by stealing and robbing on the common highways, particularly when they see these frequented by any novices of ships from Europe.

As the colony began to expand territorially, more and more detribalised indigenes from neighbouring clans swelled their ranks so that by 1672 up to 30 of their men could be put to work by the Dutch:[17]

The Governor engaged 30 Hottentots, who generally loiter about the fort in idleness, to wheel earth for the new fort, on condition of receiving two good meals of rice daily, together with a sopie (‘dram’) and a piece of tobacco; these Africans undertook the work with great eagerness.

These folk were very likely encamped at what today has recently been renamed Heritage Square. Originally known in the early colonial period as Hottentot Plein, this appropriated and contested area was later renamed Boeren Plein and in the more recent past again renamed Van Riebeeck Plein.

At the time of Zara’s suicide, there were already 41 Dutch households, many of whom were already making use of Hottentot women and child labour.

Zara’s mistress was the daughter of Ds. Nathaniel de Pape and his wife, Elisabeth Veenbergh, who had arrived at the Cape with her father and brother on 3 October 1662 on board the Orangien[18]. The family were en route to Negapatnam on the Coromandel Coast where De Pape had been appointed minister to the VOC factory there. Soon thereafter, the nubile Lydia de Pape was engaged to Hendrik Lacus on 19 October 1662.[19] They married on Sunday 29 October 1662.[20] The couple had three daughters: Lydia Lacus (baptised 2 September 1663), Henrietta Lacus (baptised Cape 23 August 1665), and Elisabeth Lacus (baptised Cape 15 December 1669).

Lydia de Pape’s voyage to the Cape was marred by the cruel actions of the skipper Pieter Crynsz: Kant against whom there were many complaints – also by her minister father, Nathaniel de Pape. Kant was accused of underfeeding the crew, preventing the surgeon and sick-visitor from performing their duties, causing thereby many unnecessary deaths.[21]

Lacus had arrived at the Cape as adelborst already in 1659. Also having a good knowledge of French, he was appointed successively: assistant, bookkeeper and secretary of the Council of Policy (1660), fiscal (1663), junior merchant (1666), secundus – ie second-in-command (1667). In 1665 Lacus gave power of attorney to Jan van Weert and Adolff Woesthoven coopluijden binnen Amsterdam to manage his inheritance from his mother Mechtelt Gunter which was being administered by his uncles Jan Woesthoven and Reijnier Tellegens. Family property amounted to 3 hoeven of 48 morgen leggende in’t landt van Gulick tusschen de steden Zittert [Sittard] ende Wassenberch [Wassenberg]. This is situated on the Dutch border (Limburg province) within present-day Germany.

On 12 September 1666 Lydia de Pape witnessed the baptism of Eva Meerhoff’s legitimate, half-Hottentot, Robben-Island-born son, Solomon, together with Joannes Coon and Pieter Klinckenburg. On 12 July 1667 Hendrik Lacus drew up his will.

The Lacus household consisted of one female slave … een Angoolse Kaffarinen … Dorothea and three male slaves: Louis van Bengale, Dorothea’s son Johannes van de Caeb[22] and one other (as yet unidentified) adult. Zacharias Wagenaer had sold Louis van Bengale to Hendrik Lacus on 25 September 1666: for Rds 80 or f 240 light money.

Accused of theft of Company goods and embezzlement of Company money to the amount of 6,865 guilders, Hendrik Lacus was suspended by Commander Cornelis van Quaelberg on 5 September 1667. He responded to the allegations against him on 17 October 1667. On 31 October 1667, his property was confiscated, including his slaves – with the exception of Louis van Bengale. This slave he was permitted to retain as a personal attendant.[23] Dorothea van Angola, now a Company slave, was to baptise several children thereafter: Cornelia halfslagh (baptised Cape 27 March 1672); Cecilia halfslagh (baptised Cape 8 September 1675); Dorothea halfslagh (baptised Cape 26 November 1679) and Claes (baptised Cape 21 April 1686).

Their house servant, the Hottentot Zara, was allowed to continue serving Lydia de Pape.[24] This appears to have been short-lived. In retaliation to Lacus’s unwillingness to co-operate with the investigation, his household was disbanded and his personal effects inventorized in his presence. His slave Louis van Bengale, now also confiscated, became a Company slave like Dorothea van Angola. It was only on 13 April 1672 that Louis was permitted to purchase his freedom in terms of a promise made by visiting Commissioner IJsbrand Goske in February 1671.[25]

Lacus was confined to the sergeant’s quarters within the Fort while it was arranged for his wife and their three children to move into a separate room at the widow Wiederholt’s place also within the Fort.[26] She was Geertruyd Mentinghs: who had just lost two husbands in recent years: Evert Ro(o)leemo and Willem Lodewyk Wiederholt. Was it at this stage that Zara joined the household of Maaij Ansela?

Lacus’s trial commenced on 2 March 1668. In terms of a resolution of the Council of Policy dated 7 March 1668, Lacus was to be detained on Robben Island. Zara and the slaves Louis van Bengale, Marij (probably Widow Wiederholt’s slave, Marij van Guinea) and the bandiet Groote Catrijn (washerwoman to the commander’s household) became part of the inquiry on 9 March 1668. Being slaves, and in the case of Zara – a Hottentot and thus a heathen – they could not give testimony under oath, such ‘evidence’ being inadmissible in judicial proceedings. Nevertheless, whatever they disclosed came to be incorporated into the interrogatories of other ‘competent’ witnesses, viz. the derde barbier Ignatius Oogst and Anthonij de Chinees. The latter being none other than the baptised former slave of Zacharias Wagenaer, Antoni van Japan.[27]

Ignatius Oogst stated that, on orders from his superior, the eerste chirurgyn Paulus Winckler, he had brought a kasje to the house of Lacus and handed it to Zara. He denied knowing what was in the chest.[28] Antoni van Japan, in turn, stated that he had received a kasje from Lacus containing sake (Japanese rice wine), money and Lydia de Pape’s best clothing. This he had buried under his table. Lacus had requested Antoni to hide the chest in safekeeping for the Cape’s former commander, Zacharias Wagenaer (Antoni’s and Louis’s former owner), who would stop over at the Cape in 1667. Of the money in the chest, he returned one bag to Lacus and the other two he fetched from Louis: one belonging to Lacus, the other obtained from the jongen of the late Pieter Meerhoff – ie the slave boy known as Jan Vos van Cabo Verde.

Antoni stated further that he had heard from Louis that Dorothea had received some money from Thielman Hendricksz:. He had also heard from Zara, Marij and Groote Catrijn that another chest had been sent away to Ceylon [Sri Lanka] with Pieter Dombaar. Louis had also said that if his master were to punish him (again?), he would turn informer and reveal the whereabouts of items hidden by Lacus. Louis had also mentioned to him how Lacus, when drunk, would physically abuse his wife Lydia.[29]

Lacus’s detention on Robben Island, if not immediately put into effect, would not have been later than 4 May 1668 when it is on record that a boat was sent to the island. His wife and children accompanied him. There they joined the recently widowed Eva Meerhoff – the Hottentot woman Krotoa – late wife to the island’s superintendent, Pieter Meerhoff, the news of whose massacre at Antogil Bay (Madagascar) had been received on the mainland on 27 February 1668. The Widow Meerhoff was to keep the Lacus family company until her own return to the mainland, together with her three Eurafrican children (the youngest being Lydia’s godson), on 30 September 1668. Eva Meerhoff would return to the island less than 6 months later. This time, however, as a detainee like Lacus.

The Lacus family’s detention on Robben Island continued for almost a year. The fact that the Cape now had a new commander, the unpopular Jacob Borghorst, (since June 1668) in no way changed their situation. On 14 March 1669, however, Lydia de Pape’s prayers to be allowed to return to the mainland were answered: [30]

… Decided to comply with the humble prayer of the wife of the junior merchant, Hendrik Lacus, to be allowed with her children to leave Robben Island for this place, on condition that she shall support herself without becoming a burden on the Company.

She and her three daughters returned to the mainland on 15 March 1669. Where did they live once on the mainland? Could they have moved in with Maaij Ansela? Would Zara have returned into Lydia’s service? On her return, Lydia would have experienced directly, the plight of her friend, Eva Meerhoff, then already incarcerated in the Fort’s Black Hole, soon to be relegated without trial, like Lydia’s husband, to Robben Island on 26 March 1669. She would have heard first hand about the confiscation of the Hottentot infant Florida from Geertruyd Mentinghs:, now married to the physically lame Dirk Bosch (from Amsterdam). Lydia’s former roommate was one of the European women who had disrupted the living child’s funeral.[31] Also, how the soon-to-die Florida and Lydia’s godson (Solomon Meerhoff) and his siblings had been dumped by the Church Council with Barbara Geems:, the brothel-keeper who was Maaij Ansela’s neighbour.[32] Lydia also soon witnessed in July 1669 the removal from office of her husband’s other friend, the heemraad Thielman Hendricksz: (from Utrecht).

On 24 August 1669 Lydia was granted permission to take her three daughters to her father, Nathaniel de Pape, in Negapatnam. She did not go, however. On 14 February 1670 she addressed the Council of Policy in person to plead her husband’s release from Robben Island. The Council agreed. Lacus returned to the mainland on 16 February 1670. Finally on 12 March 1670, the Council of Justice formally sentenced Hendrik Lacus to be degraded to the rank of soldier and to be sent to Batavia. His sentence was one of Jacob Borghorst’s last duties before his departure from the Cape. Lydia and her children accompanied her banished husband to Batavia.

Zara joins Maaij Ansela’s household

Zara probably became part of the household of Maaij Ansela and her new husband, Arnoldus Willemsz: Basson already at the time Lydia and her daughter moved in with the Widow Wiederholt at the end of January 1668. The following year there would be a concentration of Hottentots and demi-Hottentots at Barbara Geems:’s place next door. Following the untimely death of the indentured Florida and the illegal detention of Eva Meerhoff on the grounds of public indecency, tolerance for indigenes – especially the ‘detribalised’ indigenous labour force within the little colony was at an all-time low.

Like Zara’s former master (Hendrik Lacus), her new master Basson also hailed from Wesel in the Duchy of Cleves. Now the mother of her husband’s first child (Willem Basson), his lawful wife Maaij Ansela was already mother to four voorkinders: Anna de Coning, Jan van As, Jacobus van As and Pieter. Prior to her marriage and whilst still a slave belonging to Hendrik Lacus’s predecessor, the secunde Abraham Gabbema, Maaij Ansela had lived in concubinage with at least two Company officials: François de Coning (from Ghent) and Joan van As (from Brussels). Her 4th child (presumably that of Van As) had died in infancy. The newly married couple owned 80 sheep and had 1 flintlock according to the muster of 1670. Still at the lowest rungs of Cape colonial society, this family would later rise dramatically to respectability.

Basson, after leaving the Company’s service, started out as knecht for the Saldanhavaerder and innkeeper, Joris Jansz: Appel (from Amsterdam) and his wife Jannetje Ferdinandus (from Courtrai). Also in their employ was another knecht François Champelier. The latter had associations with the concubine of Maaij Ansela’s friend Groote Catrijn, Hans Christoffel Snijman (from Heidelberg), who in turn was closely associated with Maaij Ansela’s husband, Jagt. Both men joined the VOC’s Chamber of Enkhuizen. Maaij Ansela’s concubine, Joan van As, and the sergeant Willem Lodewyk Wiederholt were also in the employ of this same Chamber. Another of their associates from the same Chamber was Georg Friedrich Wrede (from Uetz), Hottentotologist par excellance. He, Joan van As, and Groote Catrijn’s other concubine, Pieter Everaerts, had all gone on ‘discovery’ expeditions into the Cape interior together with Eva Meerhoff’s husband, Pieter Meerhoff.

Was Zara’s suicide a total and utter rejection of the Dutch?

What prompted Zara to take her own life? Bredekamp makes an all too easy assumption:

‘n Algemene praktyk sedert die sestigejare was die indiensnaming van jong Khoikhoidogters wat deur hul ouers as huisbediendes deur die Hollanders in diens geneem is. Op dié wyse het die jongedogters in nouer kontak met die Europese kultuur gekom. Dié meisies het Hollandse klere gedra, Hollands en Portugees aangeleer en met die basiese beginsels van die Christelike geloof kennis gemaak. Die veranderde lewenspatroon wat hierdie dogters moes volg, het sommige in so ‘n innerlike konflik geplaas dat hul lewe ‘n tragiese wending geneem het. Die bekendste geval is dié van Eva (Kratoa [sic])…’n Minder bekende tragiese geval is dié van die jongdogter Sara. Sy het ook van kindsbeen af in die huise van die Kompagniesamptenare en Vryburger grootgeword en mettertyd vervreemd geraak van haar moeder [sic] en Khoikhoileefwyse [sic]. Sy het op jeugdige leeftyd losse verhoudings met blanke mans gehad en toe een van hulle haar in die steek laat, het sy haar aan die blanke samelewing onttrek. Oor ‘n derde vrou Cornelia wat indertyd ook as bediende by Blankes [initially Jan van Riebeeck and successive commanders] gewerk het, en later na haar tradisionele leefwyse teruggekeer het, is min bekend, behalwe [sic] dat sy Hollands goed kon praat en die name van al die goewerneurs geken het.

Bredekamp is silent as to why Cornelia should have escaped any tragedy in her life. Why is no fuss made of Cornelia as a ‘success story’? François Valentyn met Cornelia and described her as follows:[33]

In 1705 I spoke to an old Hottentot woman named Cornelia, who after living for many years in the home of the first Commander, Heer van Riebeeck, went back again to her own people, where she still is. She spoke excellent Dutch, and apart from her native dress and animal skins was so civil and well mannered as to call forth astonishment. She then appeared to me somewhere between 80 and 90 years old, and could recall all the Cape governors by name.

Valentyn states that many Cape indigenes opted to return to their own traditional lifestyles even after being in the service of Europeans for many years “… as also many such could be pointed out at the Cape”:[34]

As regards the men, these are in themselves the laziest creatures that can be imagined, since their custom is to do nothing, or very little; and this is the life of the truly free Hottentots, the owners of the land as they call themselves, regarding us as the greatest slaves in the world, with our so exactly fixed and precise way of life. If there is anything to be done, they let their women do it.

We may never know Zara’s inner turmoil or the extent of her tragedy. Had she been culturally challenged? What personal circumstances were at stake? But we have been left with one piece of recorded contemporary hearsay. Rumour had it that Zara had “hanged herself in despair because a loose Dutchman, in order to have free enjoyment of her, promised her marriage but failed of his word” – if we are to heed any of the questionable pronouncements of Willem ten Rhyne who visited the Cape in 1673.[35]

François Champelier, the man who cut down Zara’s corpse, was a bachelor until he married the widow Hans Ras / Rasch (from Angeln) who had been massacred in November 1671 by indigenes during a hunting expedition in the interior. His widow, Catharina Hustings, alias Trijn Ras, married Champelier on 17 April 1672. Could he have been romantically attached to Zara? Was it he who jilted her? Although we are free to speculate, these still remain open questions for lack of any substantial proof. Champelier, later died in June 1673 at the hands of indigenes whilst on a hunting expedition into the interior.[36]

In his book A Short Account of the Cape of Good Hope and of the Hottentots who inhabit that region (published in 1686), he claims to have actually met Zara in person, alive, and that he had spoken with her.[37] This was impossible, however, as she had already taken her own life by 1671. He also claims to have met two other aboriginal women (viz. the notorious Krotoa baptised Eva) and Cornelia whom, together with Zara, he found to be “distinguished for shrewd and subtle understanding” in contrast with the rest of “this savage and depraved people”. Characteristically, he also confuses Eva with Cornelia and vice versa:

The women may be distinguished from the men by their ugliness. And they have this peculiarity to distinguish them from other races, that most of them have dactyliform appendages, always two in number, hanging down from their pudenda. These are enlargements of the Nymphae, just as occasionally in our own countrywomen an elongation of the clitoris is observed. If one should happen to enter a hut full of women – the huts they call kraals in their idiom – then, with much gesticulation, and raising their leathern aprons, they offer these appendages to the view. A surgeon of my acquaintance lately dissected a Hottentot woman [ie Zara] who had been strangled. He observed these finger-shaped prolongations of the Nymphae falling down from the private parts, two nipples in one breast, and various stones in the pancreas.

The appropriation of Hottentot body parts as amulets or trophies is also known to have taken place:[41]

What is more, the Governor [Goske], whose word can absolutely be relied upon, added the following: “I too owned a remarkable stone. It was cut from the middle of a man’s testicle, and, on account of its diamond-like brilliance I had it set in a ring. But I made a present of it to the King of the negroes, a superstitious fellow, who displayed a profound belief in its power as an amulet.”

Autopsy

Johann Schreyer, the junior surgeon assigned the task of doing the autopsy on Zara’s corpse, hailed from Lobenstein. He joined the VOC and came to the Cape as adelborst arriving on board the Eendracht on 3 December 1668. Thereafter, he became acting junior surgeon in 1670, junior surgeon in 1671 and surgeon in 1672. He married on 24 January 1672 Jacomyntie / Jacomyntje Bakkers: (the latter name is also found as Backers: and Barkers:) of Amsterdam, the widow of the senior surgeon, meester Jan Holl. They had the following children:

(1) Johannes baptised 19 March 1673 (died in infancy)

(2) Johannes baptised 20 May 1674

Schreyer and his family, including his stepdaughter Gertruyda Hol (baptised Cape 22 March 1671), later went to India. He wrote a book in which he also gave a description of the Cape entitled Neue Ost-Indische Reisbeschreibung von Anno 1669 biss 1677 handelnde von unterscheidenen Afrikanischen und Barbarischen Völkern, sonderlich dere an dem Vor-Gebürge, Caput Bonae Spei sich enthaltenden sogenannten Hottentotten which was published in Leipzig in 1681.[42]

In his writings he makes no mention, whatsoever, of Zara or of the autopsy that he performed on her corpse. He was also the surgeon who helped perform (together with Pieter Walbrandt) the autopsy on the strangled infant of the Company slave woman Susanna van Bengale alias Een Oor on 8 December 1669.[43] Schreyer was also uniquely and strategically placed when the surviving Hottentot infant baptised Florida was exhumed alive on 24 January 1669 but who died soon thereafter in April / May that same year.[44] No record of any autopsy having been performed on Florida could be found. Was an autopsy ever performed on that occasion?

The report of the autopsy done by Jan Schreyer on Zara’s corpse has been preserved but never published.[45] On 18 December 1671 in the presence of commissioners, Schreyer cut open the corpse of a certain female Hottentot known popularly as Sara”. Externally, her face was purple and swollen like a ball. The mouth was full of foam. Around the neck a purple ring could be observed, likely to have been caused by a cord cutting into the flesh but without any external wounds being visible. Internally, blood had collected in the hollow of the chest and the lungs were full of foam and flooded with blood. The findings were indicative that the deceased Hottentot woman did not die naturally, but died a violent death due to suffocation. Of course, Schreyer makes no mention whatsoever of Zara’s one double-nippled breast and gives no discription of her dangling genital organs. There is also no mention of any pregnancy. What happened to the stones found in her pancreas?

Ick ondergeschrevene Jan Schreijer van Löwenstein onderchijrurgijn in diens van de Vrije Vereenigde Nerdelantsche g’Octroijeerde Oost-Indische Comp:[agni]e en alhier in des Fortresse de Goede Hoope in die qualiteijt, mits ‘t afsterven van den Opperchijrurgijn, alleen bescheijden hebbe ten ordre van den Achtbaeren Raad deser Residentie, op huijden den 18:en desen maant Xbris, in presentie en ten overstaen van Gecommitt[eerd]ens uijt deselve, geopent en gevisiteert het dode lichaem van seker Hottentots vrou mensch in de wandelinge genaamt Sara, en bij incisie het selve cadaver sodaenigh gevlees gevonden als volgt, te wetens het aengesicht was paers en bol opgezwollen, de mond vol schuijm, en om de hals een paerse cringh, door de insnijdinge ener koorde oft diergelyc geschiet sonder dat aen alle de buytenvleden eenigh leke van quetsingh off violentie conde bespeurt werden gelijk oock alle de doen van binnen hebbe bevonden gaeft en wel dispoort te zijn behalwen dat inde hollight der borst eene vergaderinge van bloet, en de longhe vol schuijm en met bloet onderlopen haer vertoonde uijt welcke tekenen dat voor genoemde Hottetotinne [sic] niet natuuren, maer door een geweldige doot en een suffocatie is overleden.

Aldus verclaert in d’Fortresse de Goede Hoop deses 18 Xbris 1671.

[signed] Jan Schreyer

The Trial

Zara was immediately put on trial in absentia. Rather, it was her corpse that was put on trial. Donald Moodie’s translation of the court proceedings is fairly accurate.[46]

Presentibus, – Joannes Coon, Lieut. Daniel Fraymanteau [sic] and Willem van Dieden, Members of the council of this residency. The fiscal [Hendrik Crudop] having reported to the Council, that a certain Dutch female Hottentot, had this morning hanged and thus strangled herself, in the sheep house of one of the free men, near this fortress – as shown by a declaration of the surgeon, (who, by order of the Council, had dissected the body) that the said female has died from no other probable or conceivable cause than by the violent death inflicted by her upon herself, by means of suffocation. The Council having also examined two persons namely Francois Champelaar, servant of Joris Jans:, and Angela of Bengal, wife of Arnoldus Willems:, who state that the said Hottentot was found hanging in her own gown band, fastened in the thatch overhead; and that on their first coming, they observed some motion in the veins of the neck, which induced said Champelaar to cut down the body in hopes that life was not extinct; but that, on the body falling to the ground, it was found that Satan had already taken possession of her brutal soul. It was therefore concluded-as the said female Hottentot, known by the name Sara, and about 24 years of age, had resided (verkeert) [47] from her childhood with Company’s servant or free men, and that not merely from her bare food, but also with some persons for wages, by which means she had thus long maintained herself, and had thus acquired the full use of our language and of the Portuguese, and had become habituated to our manners and modes of dress; and as she had also frequently attended Divine service, and had furthermore, (as is presumed) lived in concubinage with our, or other German people[48] not having any particular familiarity with her kindred or countrymen; which is the case also with her mother, who also maintains herself by earning daily wages among our inhabitants – That, from the said allegations and reasons, it is concluded that the said Hottentot can not be any longer considered as having led the usual heathenish or savage Hottentot mode of life, but to have entirely relinquished the same, and adopted our manners and customs (levens- en lantsaardt) and that accordingly, she had enjoyed, like other inhabitants, our protection, under the favour of which she had lived; as this animal (bestie) then, has not only-actuated by a diabolical inspiration-transgressed against the laws of nature, which are common to all created beings; but also-as a consequence of her said education-through her Dutch mode of life-against the law of nations, and the civil law-for, having enjoyed the good of our kind favor and protection, she must consequently be subject to the rigorous punishment of evil ; seeing that those who live under our protection, from whatever part of the world they may have come [sic], and whether they be christians or heathens, may justly be called our subjects – And and this act was committed in our territorium , and in a free man’s house under our jurisdiction; which should be purified from this foul sin, and such evil doers, and enemies of their own persons and lives visited with the most rigorous punishment. It is upon these grounds claimed and concluded by the fiscal, that the said dead body, according to the usages and customs of the United Netherlands, and the general practise (ingevoer) of the Roman law, be drawn out of the house, below the threshold of the door, dragged along the street to the gallows, and there hanged upon a gibbet as a carrion for the fowls, and the property of which she died possessed confiscated, for the payment, therefrom, of the costs and dues of justice.

The court, having heard the arguments advanced in support of the conclusion of the fiscal, and attended to every thing relative to this matter;- accedes to the conclusion and claim of the officer, including the execution of the same.

In the Fortress the Goede Hoop: datum ut supra.

The court that tried Zara consisted of only three men Joannes Coon, Daniel Froymanteau, Willem van Dieden. Coon was one of the men who tried the Company slave woman and convict Susanna van Bengale, alias Een Oor, while Van Dieden was the second husband of Grietje Frans: Meeckhoff who had been one of the European women who had discovered and prevented the Hottentot infant Florida from being buried alive with her dead mother . The fiscal was none other than Hendrik Crudop (from Bremen). He was brother-in-law to the Cape’s resident minister Adriaen de Voogd who had been instrumental in confiscating Florida and the Meerhoff children and securing the illegal and indefinite detention of Eva Meerhoff.

Crudop had arrived at the Cape in 1668 as a midshipman on board the d’Amiata. He had been steward to three successive commanders Cornelis van Quaelbergen, Jacob Borghorst and Pieter Hackius. In 1669 he became assistent aan de pen and seneschal. In 1671 he combined the duties of fiscal and accountant. This was not because it was the Company’s policy to economize, as claimed by Dutch historian Gerrit Schutte.[49] From the time of the very unpopular commander Jacob Borghorst, there was a chronic shortage of competent officials.

Following Commander Pieter Hackius’s death and the appointment of Governor IJsbrand Goske as his successor, there followed an awkward interregnum in the colonial administration of the Cape of Good Hope. This was to last for 10 months. The colony had been placed under the provisional administration of Daniel Froymanteau, assisted by the aristocrat Conrad von Breitenbach, Joan Coon and the omnipresent Hendrik Crudop.[50] The provisional administration was to last 4 months until the arrival of the newly appointed secunde, Albert van Breughel, on 23 March 1672. The interregnum was to last for another dramatic 6 months until 2 October 1672 when Goske finally assumed office as the Cape’s first governor.

It is a curious fact that Zara’s trial took place at a critical stage of Dutch colonisation of the Cape of Good Hope and at a time when Dutch / Khoena relations were deteriorating rapidly. The colonial administration was clearly unable to control the growing illegal trade between colonist and indigene.[51] This situation was being exacerbated by the fact that more and more ‘visiting’ indigenes were increasingly aggressive in their dealings with the occupying Dutch. The Dutch, in turn, retaliated by assaulting indigenes and taking hostages wherever, whenever and whomever – with and without authorisation.[52] This was also the start of a disappearances of Europeans whilst hunting and trading illegally in the interior, either being killed by wild animals or murdered by indigenes.[53] Finally, the ‘degenerate’ Widow Eva Meerhoff remained in banishment on Robben Island while the products of her labours were in the custody of a brothelkeeper with the blessing of the minister Adriaan de Voogd (brother-in-law to Hendrik Crudop) and his Church Council.

With the charged political atmosphere as sketched above, Zara’s contemporaneous trial cannot be viewed in isolation. Historian Robert Ross, analysing the judicial aspects of Zara’s trial, claims that “no motives of revenge and scarcely any of setting an example played a role in the arguments as to the treatment of her corpse”.[54] This is questionable and needs to be re-evaluated. The raison d’être for the traditionally (European) prescribed punishment of impalement was deterrence – in this case not only to the Dutch, but also the insouciant indigenes resident within the colony, and even those threatening the colony from without.

It is indeed so that the court accepted this “mixture of natural law ideology and the concepts territorial jurisdiction” as justification for dishonouring Zara’s corpse. The suggestion, however, that the court was comprised of competent judicial officers as part of a stable colonial administration ‘applying their minds’ to a unique but weighty problem cannot be sustained in the light of all the various disruptive events taking place at the time and the responses of a provisional skeleton-staffed colonial administration without even a commander or secunde:

In a certain sense this case was most exceptional. Presumably because it was forced upon them in what was still a very small, face-to-face community, Dutch authorities were persuaded that they had to take action in a case where the criminal and the victim were both Khoi, or rather where they were both the same individual.

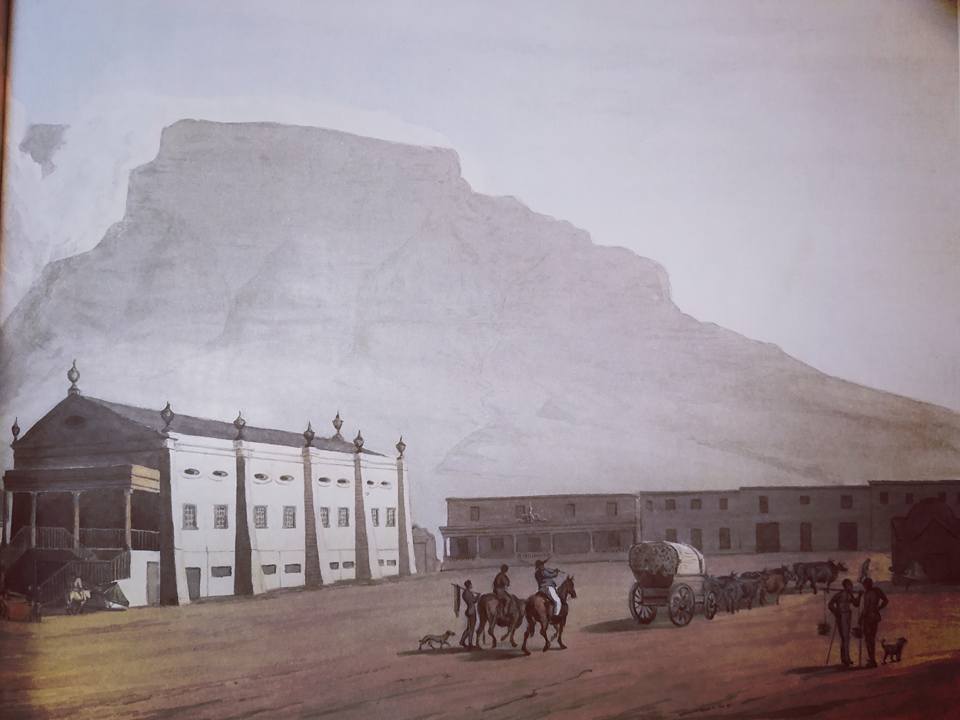

The events that followed Zara’s impalement point to very definite motives for revenge and certainly the setting of an example. The visual and violent disfigurement of Zara rotting against the backdrop of Table Mountain must have sent out exceptionally powerful signals to the indigenous people of the Cape of Good Hope. The administrative hiatus allowed the men temporarily in charge to disregard momentarily, the VOC’s official policy of non-aggression against the ‘free’ indigenous people of the Cape. Or was it just a case of ‘crisis management’? Significantly, when Magister Daniel Froymanteau died on 12 April 1672, his administration was found to be in shambles:[55]

This night the Junior Merchant Daniel Troymanteau [sic], who arrived here in the Zierikzee, and in consequence of the misfortune of Cornelis de Cretzer, had been kept here by the late Commander Hackius, after a few days illness died in the flower of his life. He had been acting as provisional Commander (since the death of Mr. Hackius), but after his death matters were found to be in great confusion, and the books quite white (not written up), so that we shall have our hands full again.

Significantly the very next day a resolution to legalise (albeit very belatedly) Dutch residency at the Cape in terms of International Law, was passed by the acting commander Albert van Breughel and his council at the insistence of the visiting commissioner, Arnout van Overbeke. This was a crucial turning point in Dutch / Khoe relations. The Dutch were most uneasy about their legally tenuous occupation.

Een vuyl nest … the rot sets in …

At this critical stage Hendrik Crudop appears to have seized the opportunity to ensure Dutch supremacy at all costs. Zara’s conviction, albeit post mortem, paved the way for yet another unprecedented arraignment, this time of live indigenes on 10 January 1672:

Five evil disposed Hottentoos were brought in by the mounted guard, fastened together. The guard stated that the prisoners had laid hold of a certain burger’s shepherd, who was herding his sheep near the guard house, forcibly rifled his pockets of all their contents, and made off with a large portion of his flock, but were pursued and overtaken by the mounted guard, who rescued the prey out of their thievish hands .

Dutch motives for revenge and setting an example are stated unequivocally in the Journal on 11 January 1672:

Some Hottentoos brought, by way of ransom for the five prisoners, eight fine young cattle, and eight sheep, but were sent back unheard; for the insolence of those people begins to get beyond bounds and insufferable, and requires an exemplary punishment to deter others, more particularly as the prisoners are subject to the chief Gonnema, through whose means two of our burgers [Han Ras and Gerrit Jans: van Rote – Rot in Upper Swabia] were so cruelly massacred last year.

This is the first time that we find the Gonnema, alias the Black Captain, being held responsible for the massacre of the two burghers. War had become inevitable by 13 January 1672:

All the burgers were mustered in arms to the number of 93; it was a pleasure to see how well they handled their infallible weapons.

The situation remained tense as evidenced by the Journal entry of 5 February 1672:

Those interested for the five detained Africans again offered a large number of sheep and cattle for their release; their offers were rejected as before, and it is intended soon to let them feel something else, for their arrogance begins to be too great.

On 10 February 1672 the Council of Justice sat to try the five indigenes:

The Council of the Fort, with the assistance of the Burgerraden, held a Court for the trial of the five Hottentots before mentioned, and after examination, 3 of them were sentenced to be flogged and branded, and banished to Robben Island, ad opus publicum in chains for 15 years; and the two others, who were not equally guilty, but were only voluntary accomplices in the theft of the sheep, were sentenced to be also well flogged, and banished to the said island for 7 years, as may be seen by the criminal roll.

The man who had just prosecuted Zara’s corpse was again prosecuting (persecuting?) officer. Once again, Hendrik Crudop came into his own. Though the indigenes appeared at a glance to be “more beast than man”, he argued (quoting numerous legal authorities), it was beyond doubt that they had the form of rational creatures. Hence they possessed rational souls. All such beings had been endowed by their Creator with a knowledge of Natural Law (the judgement necessary to distinguish right from wrong) and the Law of Nations (law common to all people). It was thus appropriate for the council to try these indigenes under ‘universal’ codes.[56] The court agreed. Their sentence was carried out on 11 February 1672:

The five Africans sentenced yesterday, were this morning, about 11 a.m. brought to the place of execution (after their sentence had been solemnly read in front of the fort) and severely punished for their crime, as above stated; meantime others of that people offered for sale seven good sheep, which were added to our flock for the usual merchandize.

On 18 February 1672 the sentenced Hottentoos were sent to Robben Island where they joined their kinswoman, the banished Eva Meerhoff. A desperate Albert van Breughel assuredly knew that the ‘die’ had been cast and that things would not quite be the same again at the Cape of Good Hope. Visiting commissioner, Aernout van Overbeke (1632-1674), returning from the East, captured the mood of the times. Already in July 1668 he had stopped over at the Cape en route to the East, taking the former commander, Cornelis van Quaelbergen with him and having unpleasant altercations with the new commander, Jacob Borghorst. 0n 23 April 1672 Van Overbeke wrote the following poem on confronting Van Breughel’s exasperation whilst in ‘control’ of the Cape of Good Hope:[57]

‘t Hooft van het Hooft de Goede Hoop,

Vondt alle dingen over hoop:

En vroegh my, wat voor raedt ick hem daar in kon geven?

Ick seg; mijn vriendt, ‘t is een vuyl nest:

Gedult te hebben, is hier best;

Wijl ghy gedwongen zijt, op Goede Hoop te leven.

END NOTES

[1] See Mansell G. Upham, ‘Maaij Ansela and the black sheep of the family – a closer look at the events surrounding the first execution of a free-burgher in Cape colonial society for the murder of a non-European’, Capensis, No. 2 (1998), pp. 33-34.

[2] Janet Todd (ed.), Mary & Maria by Mary Wollstonecraft / Matilda by Mary Shelley (Penguin, Harmondsworth 1992), pp. xxii-xxiv.

[3] H.C.V. Leibbrandt, Précis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope: Journal (W.A. Richardson & Sons, Cape Town 1902), p. 134.

[4] CA: 1/STB 18/154 Notariële Verklaringe, 4.10.1703; MOOC 3/3 Inkomende Briewe, Landdros en Heemrade – Weesmeester, 16.10.1703.

[5] Dr A.M. Hugo, Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek (Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria), Vol. I, p. 867.

[6] H.C.V. Leibbrandt, Journal 1699-1732, pp. 75-76.

[7] Report handed in to the Governor-general and Council of Netherlands India by Pieter de Vos, ordinary, and Hendrik Bekker, extraordinary Councillor of India, concerning the quarrels which have occurred between Mr. Willem Adriaan van der Stel, Governor of the Cape of Good Hope, and various freemen there (dated 18 September 1706). [H.C.V. Leibbrandt, Précis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Letters Received, p. 428].

[8] H.C.V. Leibbrandt, Journal 1699-1732, p. 270.

[9] Maurice Boucher, French speakers at the Cape in the first hundred years of Dutch East India Company rule: The European background (University of South Africa, Pretoria 1981), pp. 251-252.

[10] For a case concerning attempted suicide, see Mansell G. Upham, ‘The First Chinese and Japanese at the Cape, Capensis (No. 2 (1997), pp. 11-12.

[11] Eg. … Ringe, alias Sionko from Malabar committed suicide by hanging himself [VC 23, Journal 31 October 1728] in October 1728 – a practice associated with slaves from Madagascar …

Hans F. Heese, Kronos, Vol. 11 (1986), p. 10

[12] Premesh Lalu, ‘Sara’s Suicide: History and the representational limit’ Kronos , No. 26 (2000), p. 91.

[13] Dapper (1668) featured in I. Schapera & B. Farrington, The early Cape Hottentots described in the writings of Olfert Dapper (1668), Willem ten Rhyne (1686) and Johannes Gulielmus de Greyvenbroek (1695), (Van Riebeeck Society, Vol. 14, Cape Town 1933), pp. 60-61.

[14] The following historians have written very briefly about Sara. They never, however, make the connection that the Hottentot servant in the Lacus household known as Zara / Sara, was in fact the same person as the Cape indigene Zara who committed suicide: Dr Anna J. Böeseken Uit die Raad van Justisie, 1652-1672 (Government Printer, Pretoria 1986), pp. xiv no 421, 194 & 204 & Slaves and Free Blacks at the Cape 1658-1700 (Tafelberg, Cape Town 1977), pp. 90-91 & 97; Prof. J. Leon Hattingh, ‘Die Blanke Nageslag van Louis van Bengale en Lijsbeth van die Kaap’ Kronos (1980), pp. 6-7 & Die Eerste Vryswartes van Stellenbosch 1679-1720 (University of the Western Cape, Bellville 1981), pp. 24-25 and Dr G. Con de Wet, Die Vryliede en Vryswartes in die Kaapse Nedersetting 1657-1707 (Historiese Publikasie-Vereniging, Cape Town 1981), p. 211. Likewise, the following academics, researchers and writers all briefly recount Sara’s suicide and trial but never connect her to anybody or to any particular colonial household: I. Schapera & B. Farrington (1933); Victor de Kock, Those in Bondage (1973); Major R. Raven-Hart, Cape Good Hope 1652-1702: The First fifty years of Dutch colonisation as seen by callers (A.A. Balkema, Cape Town 1971); Richard Elphick & Robert Shell, The Shaping of South African Society (1977); Henry C. (Jatti) Bredekamp, Van Veeverskaffers tot Veewagters: ‘n Historiese ondersoek na betrekkinge tussen die Khoikhoi en die Europieërs aan die Kaap, 1662-1679 (University of the Western Cape, Bellville 1981); Robert Ross, Beyond the Pale: Essays on the History of Colonial South Africa (Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg 1982), pp. 169-170; Prof. P.J. Coertze, Die Afrikanervolk en die Kleurlinge (HAUM, Pretoria 1982), pp. 67 & 121; Richard Elphick, Khoikhoi and the founding of White South Africa (Ravan Press, Johannesburg 1985); Frances Karttunen, Between Worlds: Interpreters, Guides, and Survivors (Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey 1994); Carmel Schrire, Digging through darkness: Chronicles of an Archaeologist (Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg 1995) & Premesh Lalu, ‘Sara’s suicide: history and the representational limit’ Kronos (Journal of Cape History), No. 26 (2000), pp. 89-101.

[15] Jan van Riebeeck: Memorandum to Zacharias Wagenaer, dated 5 May 1662 [Donald Moodie, The Record or a series of official papers relative to the condition and treatment of the Native tribes of South Africa (1838) (A.A. Balkema, Cape Town 1960, p. 247].

[16] Zacharias Wagenaer, Memorandum to Cornelis van Quaelbergen 24 September 1666. [Donald Moodie, The Record, 291].

[17] Journal (7 October 1672).

[18] Also known as the Oranje .

[19] … Heden hebben haer in ondertrouw begeven Hendrick Lacus van Wesel, boeckhouder ende secretaris deser Fortresse, ende Lijdia de Pape, dochter van den Eerwaerdigen en Godtsaligen dome. Nathaniel de Pape, predicant op het hier jonghst aengewesen schip Orangien … [Journal of Zacharias Wagenaer, p. 29].

[20] … Naer ‘t ordinaris sermoen zijn wettelijck getrouwt de persoonen die haer op den 19en deses in ondertrouw hadden gebeven … [Journal of Zacharias Wagenaer, p. 31].

[21] H.C.V. Leibbrandt, Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Attestations, pp. 455-457 (12/13 October 1662).

[22] Baptised at the Cape 23 May 1667.

[23] Anna J. Böeseken (ed.), Resolusies van die Politieke Raad, Vol. I, pp. 362-363 (resolution dated 31 October 1667).

[24] Dr Anna J. Böeseken (Slaves and Free Blacks at the Cape 1658-1700) (1977), pp. 90-91), read incorrectly into this resolution that Sara was the ‘wife’ of Louis van Bengale. This misconception has been perpetuated by Dr G. Con de Wet (Die Vryliede en Vryswartes in die Kaapse Nedersetting 1657-1707 (1981), p. 211). Prof. J. Leon Hattingh (‘Die Blanke Nageslag van Louis van Bengale en Lijsbeth van die Kaap’, Kronos (1980), pp. 6-7 & Die Eerste Vryswartes van Stellenbosch 1679-1720 (1981), pp. 24-25), however, pointed out that Louis van Bengale would have been too young at the time for Sara to be his concubine. Instead, he suggested that Hendrik Lacus himself may have been Sara’s concubine. A careful reading of the resolution confirms simply that Hendrik Lacus had been allowed to retain the services of Louis van Bengale, whilst his wife [ie Lacus’s wife and not that of Louis van Bengale] would be allowed to keep the … d’Hottentottinne Zara … in her service.

[25] Anna J. Böeseken, (ed.), Resolusies van die Politieke Raad, Vol. II, p. 82. (resolution dated 13 April 1672).

[26] Anna J. Böeseken (ed.), Resolusies van die Politieke Raad, Vol. 1, 1651-1669, p. 365 (26 January 1668).

[27] Mansell G. Upham, ‘The First Recorded Chinese & Japanese at the Cape’, Capensis, No. 2 (1997), pp. 10-22 & ‘In hevigen woede … GROOTE CATRIJN: earliest recorded female convict at the Cape of Good Hope – a study in upward mobility’, pp. 21-22.

[28] CA: CJ 2952, pp. 194-196 (Interrogatory of Ignatius Oogst dated 7 & 9 March 1668).

[29] CA: CJ 2952, pp. 214-217 (Interrogatory of Anthonij de Chinees who signed his name Ant(h)oni van Japan dated 7 & 9 March 1668).

[30] H.C.V. Leibbrandt, Journal 1662-1670 (14 March 1669), p. 269.

[31] Mansell G. Upham, ‘In Memoriam: FLORIDA (born 23 January 1669- died April 1669): Mythologising the Hottentot ‘practice’ of infanticide – Dutch colonial intervention & the rooting out of Cape aboriginal custom’ Capensis, No. 2 (2001), pp. 5-22.

[32] Maaij Ansela’s property in Cape Town’s Block C and Barbara Geems:’s property in Block B both bordered on the Heere Straat (present-day Castle Street).

[33] Beschrijvinge van de Kaap der Goede Hoop, 1726, (Van Riebeeck Society Part II second series No. 4, Cape Town 1973) pp. 72-73.

[34] Beschrijvinge van de Kaap der Goede Hoop, 1726, pp. 70-75.

[35] I. Schapera & B. Farrington, The early Cape Hottentots, pp. 124-127.

[36] Mansell G. Upham, ‘Beat the Dogs to death! Beat the Dogs to death!: Making a moordkuil of our hearts – the Moordkuil Massacre and its Manifestations’, (unpublished paper delivered to the Genealogical Society of South Africa (Western Cape Branch) 19 march 1996.

[37] I. Schapera & B. Farrington, pp. 124-127.

[38] … De Qua sup: quam amicus chirurgus dissecuerat … Concerning whom [ie Sarah] see above. She was the one my friend the surgeon dissected …

[39] Cape Archives (CA): C 2397 (18.12.1671).

[40] I. Schapera & B. Farrington, pp. 114-115.

[41] Ten Rhyne quoted in I. Schapera & B. Farrington, p. 115.

[42] See J. Hoge, Personalia of the Germans at the Cape (Cape Archives Year Book 1946), p. 37 & R. Raven-Hart, Cape Good Hope, Vol. I, pp. 114-139.

[43] Mansell Upham, ‘Consecrations to God: The nasty, brutish and short life of SUSANNA FROM BENGAL – otherwise known as ‘ONE EAR‘ – the Cape of Good Hope’s 2nd recorded female convict’, Capensis, No. 3 (2001).

[44] Mansell G. Upham, ‘In Memoriam: FLORIDA, Capensis, No. 2 (2001), p. 13.

[45] CA: C 2397 (18 December 1671), pp. 133 or 20 or 193.

[46] He fails, however, to mention the fact that it was in Maaij Ansela’s sheep pen that the corpse had been found hanging.

[47] The word verkeert is used which is closer to involvement, or having dealings or intercourse with. The word is telling…

[48] … onse, ofte andere Duytse natien … [Note: Duytse is used here in the ethnic sense: Germanic ].

[49] Dictionary of South African Biography, Vol. III, p. 188.

[50] Resolution dated 1 December 1671.

[51] This is evident from Hendrik Crudop’s placcaat of 3 December 1670 forbidding the colony’ inhabitants to go beyond the outposts without permission and also from the various judicial arraignments of inter alia Thielman Hendricksz:’s wife, Mayke Hendriks: van den Berg (14 January 1671), Jacob Cornelisz: Rosendael (27 May 1671), and Frans Gerrits: Noortlander (18 November 1671).

[52] See the Journal entries for 16 January 1671, 8 July 16471, 10 August 1671 and 16 August 1671.

[53] See the Journal entries for 7 September 1671, 16 September 1671, 12 October 1671, 30 October 1671, 21 November 1671 and 28 November 1671.

[54] Robert Ross (African Perspectives 5 (1982) 7-37 [see also ‘The Changing Legal Position of the Khoisan in the Cape Colony, 1652-1795’, Chapter 8 of Beyond the Pale: Essays on the History of Colonial South Africa, 1994)].

[55] H.C.V. Leibbrandt, Précis: Journal 1671-1674 & 1676, p. 51.

[56] CA: CJ 282, pp. 37-63 & Richard Elphick, Khoikhoi and founding of White South Africa, p. 184.

[57] IN HET STAMBOECK VAN DEN HEER AELBRECHT VAN BREUGEL; COMMANDERENDE AEN CABO DE BOA ESPERANZA: Daer hy (een dagh voor my gekomen) alles in ‘t Wilt vondt; waar over sich dickwils aen my beklaegde: den23 April, Anno 1672.

[…] ZARA (c. 1648-1671) – An inquiry into the (mis)application of traditionally prescribed punishm… […]

LikeLike

[…] ZARA (c. 1648-1671) – An inquiry into the (mis)application of traditionally prescribed punishm… […]

LikeLike

[…] ZARA (c. 1648-1671) – An inquiry into the (mis)application of traditionally prescribed punishm… […]

LikeLike

[…] [3] https://mansellupham.wordpress.com/2020/05/16/zara-c-1648-1671-an-inquiry-into-the-misapplication-of… […]

LikeLike

[…] ZARA (c. 1648-1671) – An inquiry into the (mis)application of traditionally prescribed punishm… […]

LikeLike