by Mansell G. Upham ©

“It was felt that these people could not possibly remain without clothing in this cold country, as they would perish …”

The Prince of Java, the pangerang, Dipa Nagara – banished (16 August 1723) ex Batavia [Jakarta, on Java, Indonensia) by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to the Cape of Good Hope – requests (3 May 1724) the Council of Policy at the tip of Africa that he may be allowed as much clothing for himself and his people [nine in total] as is given to the Company’s slaves:

… Laastelijk is door den Edelen Heer Gouverneur [Maurits Pasques de Chavonnes] te kennen gegeven hoe den hier gerelegeerde Pangerang Dipa Nagara aan Zijn Edele nogmaals hadde betuijgt dat het hem langer onmogelijk was met desselfs gevolg te kunnen subsisteeren, dat desselfs broeder, den Pangerang Loring Passer, daar omtrent alles bijgebragt hebbende wat hij konde, insgelijx niet langer in staat was hem of de zeijne eenige verdere hulpe of assistentie toe te brengen, tot welkers ontlastinge ook nu bereijts met de zijne eenigen tijt herwaarts zig beholpen hadde met het nuttige van sprinkhaanen en andere gedierte, dog zulx niet langer konnende als omme godswille hadde gebeeden met eenige assistentie van speijs en kleedinge, immers zoo veel als de geringste van ‘s Comp[agnie]s. slaven quamen te genieten, mogte geholpen en bij gestaan werden, op dat hij en de sijne niet gehouden waren van honger, koude en gebrek verloren te gaan, dierhalven in overleg geevende of daaromtrent niet eenige reflexie behoorde gemaakt te werden,

Zoo is, diesaangaande gedelibereerd zijnde, goedgevonden dat tot voorkominge van wanhoop en verdere ongelucken die daar uijt zoude kunnen resulteeren, aan hem en de zijne ijder maandelijx zal werden verstrekt 40 lb. rijst, zoo als aan ‘s Comp[agnie]s. slaven werd verrigt, en dat tot beetere deckinge van haar lichaam tegens de aannaderende koude, aan haar zal werden afgegeven zoodanige kleedinge als aan ‘s Comp[agnie]s. lijfeijgenen werd verrigt.

Maurits / Mauritz Pasques de Chavonnes (1654–8 September 1724) – governor of the Cape of Good Hope (1714-1724)

The request is finally granted (4 June 1724) …

The Mataram pangerang (‘prince’) Dipa / Diepa Nagara / Dipanagara / Diponegoro is banished (16 August 1723) to the Cape with two wives:

- radeen Ajoe Daba &

- radeen Ajoe Badrie,

three sons:

- Doerik,

- Amir &

- Soubawa / Loubawax

and three female servants:

- Boele,

- Derpa &

- Kebben

He and his entourage arrive (1 December 1723) together with 15 other exiles on the VOC ship d’Herstelling …

They are preceded by his elder brother the pangerang Loring Passer / Passir who – banished earlier to the Cape of Good Hope for life – arrives (1715) on the Gansenhoeff with two wives, his mother-in-law and nine attendants.

They are sons of the VOC puppet ruler, the Susuhunang / Soesoehoenan (’emperor’) of Mataram Sampeyan Dalam ingkang Sinuhun Kanjeng Susuhanan Ratu Prabhu Pakoe BoewoenoI Senapati ing Alaga Ngah ‘Abdu’l-Rahman Saiyid ud-din Panatagama [Sunan Puger], the Soesoehoenan of Mataram:

Pakubuwana / Pakoeboewono I (1648-1719), formerly radin Mas Drajat, later pangeran Puger and later self-proclaimed Susuhunan ing Alaga who is the younger son to Amagkurat I and the brother to Amangkurat II, uncle to Amangkurat III (dies on Ceylon [Sri Lanka] in exile 1734), and father to Amangkurat IV.

These exiles are sent to live at the Cape’s new colony at Stellenbosch where they join his brother`s household with the VOC providing exiled royals with housing, a monthly allowance and food rations, such as rice. Provision had been made for his brother’s household to move into the requisitioned house of the oud-heemraad Daniel Pfeil (from Karlskrona in Sweden). Situated at the lower end of Stellenbosch’s present-day historical Dorp Street, the land – originally the “Companjie’s huys en land dat door de Pangerang Laning Paffin [sic] is bewoond en gebruikt geweest” – later, when transferred (4 January 1794), becomes known as Lambert Fick’s Farm after its new owner.

A portion of this land, together with portions of:

- an original grant (1 May 1793) to Gustaf / Gustav Andersson (from Värmland, Sweden) – Landdrost of Stellenbosch and Drakenstein – who married Catharina Elisabeth Möscher (daughter of Ulrich Möscher from Copenhagen, Denmark and his Cape-born wife Catharina Maria Hoffman) – a portion of which is sub-divided and sold to Rev. Meent Borcherds becoming part of La Gratitude

- a portion of Vredelust – originally part of Libertas granted to an earlier ancestor Jan (‘Bombam’) Cornelisz: from Oud-Beijerland in Zuid-Holland (transferred 17 May 1804)

become consolidated as a new erf – 59 Dorp Street – which passes (26 October 1876) to the KRIGE Family [Issie (‘Ouma’) SMUTS’s grandfather and later to her father].

The erf – initially known as Magnolia – is later inhabited by the cabinet maker George John HOLLOWAY (1836-1920) and his family.

He was the older brother to my maternal great-great-grandfather Henry Edward HOLLOWAY (1839-1921).

Thereafter – now renamed Casa Bianca – the erf becomes the rented residence of my paternal great-grandfather, the tailor, Matthys (‘Silwervis’) Michiel BASSON (1866-1942) and his family. Sadly, much later, the old Cape Dutch house is needlessly demolished (1973) to make way for the present-day “Robb Motors” [situated directly opposite Oom Samie se Winkel] …

According to a secret resolution of the Council of India (Castle of Batavia, Monday 16 August 1723), it is ruled that:

Diepa Nagara who is of a quite different and less important stature, accompanied by his family, is to be exiled to the Cape of Good Hope as soon as possible. There he is to earn a living together with his brother Loring Passir. He is not worthy of any more mercy, seeing that even during the reign of his father [Pakubuwana I] he and his brother Dipa Santah had defected to the `rebels` [the interior regencies in East Java – Ponorogo, Madiun, Magetan, Jogorogo, where Diepa Nagara is sent by his father to suppress the rebellion in the eastern interior but instead he joins the rebels assuming the messianic title of Panembahan Herucakra]. Dipa Santah is imprisoned by their brother Mankoerat (also called Amancoerat), who becomes ’emperor’ [Amangkurat IV] after the demise [1719] of their father [Pakubuwana I]. As punishment for his behaviour, Dipa Santah is strangled by order of His Majesty who informs the VOC government of the sentence in writing.

Pangerang Dipenegoro outlives, not only his older brother, but also all his wives, sons and their three attendants who all die at the Cape.

During this time, he petitions (1 February & 2 February 1743) to be repatriated with his wife, son and four grandsons [Cape Archives (CA): C 242 Requesten en Nominatiën, 2.2.1743, 1.2.1743 en ongedateer, pp. 105, 109-110, 113-114, 117-118, 121-122, 125-126, 129-130, 133, 135-136, 139-140, 143-144, 147-148, 151-152, 155-156, 159-160, 163-164, 169-170, 173-174, 177-178 en 181-182][Resolution of Council of Policy (14 February 1743)]:

Dipa Nagara (Pangerang, or Prince) had arrived here with his followers in the Herstelling in 1723, having been sent away by his brother from India, to remain away as long as the latter lived that he might be rid of him for good; his brother is already dead 16 years, but as yet he has not received back his liberty, he therefore begs Gov.[ernor] Gen.[eneral] Imhoff and the Gov.[erment] and Council here to have mercy on him, and permit him to return to Batavia with his wife, son, and his four grandsons (Signature attached) (CA: Requesten No. 26)

Gustaaf Willem, Baron van Imhoff (8 August 1705-1 November 1750) – VOC Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies (1743 – 1750)

Three years later, Dipa Nagara (Pangerang) petitions (1746) the Cape Goverment to emancipate his female slave Roenga of Bengal offering as security the mandoor Jan Gagen and the Javan Wargajoso [Requesten (No. 61) (1746)].

Only after most of his family and followers die, is he finally allowed to return with his remaining followers to Java in terms of a resolution by the Cape of Good Hope`s Council of Policy (25 October 1746):

Ook is aan den Pangerang Dipa Nagara in opvolginge van de aan hem hiertoe verleende Permissie bij haar Hoog Edelens tot Batavia toegestaan om met Sijn gevolg met een der aanweesende Scheepen na derwaarts te mogen te rugge keeren, des sal met desselfs uijtrustinge sodanig worden gehandeld als men gewoon is bij diergelijke geleegentheeden, met Bannelingen van Sijn Soort alhier te doen.

A surviving Dipa Nagara and his deceased princely entourage are recorded (16 August 1723) in the Annotation Book of the Convicts from Batavia as well as Ceylon arriving here (1722-1757) [CA: CJ 3186, no. 1):

1723

On board the ship d’ Herstelling according the resolution of Governor-General and the Council dated 16 August 1723 banned to this place, namely:

Pangerang Dipa Nagara [na Batavia weedergegaan] – words in brackets written in another handwriting

| dood Radeen Ajoe Daba | his wives |

| dood Radeen Ajoe Badrie |

| dood Doerik | his sons |

| dood Amir | |

| dood Soebawa |

| dood Boele | female servants [na Batavia] – words in brackets written in another handwriting |

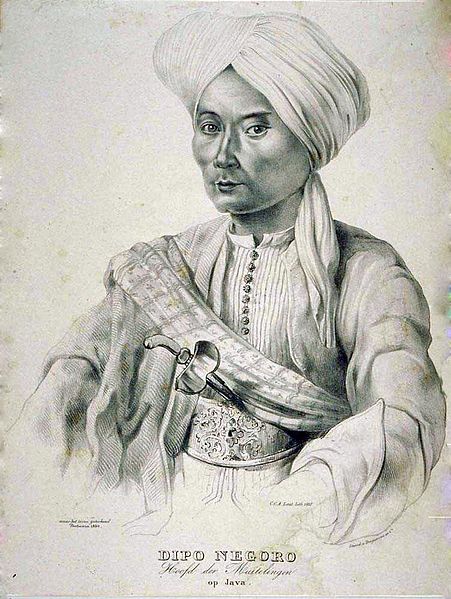

He is not to be confused with a later namesake Diponegoro / Dipanegara (Mustahar / Antawirya (11 November 1785 – 8 January 1855) – a related Javanese prince who later opposes Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia, playing an important role in the Java War (1825–1830), whom the Dutch exile (1830) to Makassar and who features in an Afrikaans poem by C. Louis Leipoldt (1880 – 1947) …

XIII Diepa Negara

Wie meely oor het in sy manlik’ hart

Vir moedige misslag en mislukte doel;

Wie vir ‘n vyand self erbarming voel

In diepste neerlaag en in droefste smart;

Wie weet hoe ru die Noodlot ons kan tart;

Hoe vryheidshartstog in die hart kan woel;

Hoe sonde deur berou word afgspoel;

Hoe rassetrots die reinste siel verswaart –

Gee hom ‘n woord van eerbewys, want hy

Het geprobeer met moed, misluk met moed

En kloek, sy harde noodlot getrotseer.

Nie syne nie die lot te lewe vry

Ná braaf geofferde heldekrag en –bloed;

Net dit te win – die meely wat hom eer!

– C. Louis Leipoldt (1880-1947), ‘Uit My Oorsterse Dagboek’, Versamelde Gedigte (Tafelberg Kaapstad 1980), p. 180

Prince Diponegoro aka Dipanegara [born Bendara Raden Mas Mustahar; later Bendara Raden Mas Antawirya] (11 November 1785 – 8 January 1855)

Javanese prince who opposes Dutch colonial rule and eldest son of Yogyakartan Sultan Hamengkubuwono III by Mangkarawati playing an important role in the Java War (1825-1830) – after his defeat and capture, he is exiled to Makassar, where he dies (1855), his five-year struggle against Dutch control of Java makes him a celebrated latter-day Indonesian national hero inspiring Indonesian Nationalists and fighters during Indonesia’s National Revolution.

Born (11 November 1785) in Yogyakarta, eldest son of Sultan Hamengkubuwono III of Yogyakarta. During his youth at the Yogyakartan court, witnesses the dissolution of the VOC, the British invasion of Java, and the subsequent return to Dutch rule. During the invasion, Sultan Hamengkubuwono II, is deposed (1810) in favour of Diponegoro’s father, using general disruption to regain control. Again deposed (1812) however, his father is once more removed from the throne and exiled off-Java by British forces. Diponegore acts as adviser to his father providing aid to British forces so that Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles, FRS (5 July 1781 – 5 July 1826) offers him the throne which he declines as father is still reigning sultan.

When the sultan dies (1814), Diponegoro is passed over for succession to throne in favour of his younger half-brother, Hamengkubuwono IV (r. 1814-1821), who is supported by the Dutch despite the late Sultan’s urging for Diponegoro to be next Sultan. A devout Muslim, Diponegoro is alarmed by the relaxing of religious observance at his half-brother’s court in contrast with own life of seclusion, as well as by the court’s pro-Dutch policy.Famine and plague spread (1821) in Java.

Hamengkubuwono IV dies (1822) under mysterious circumstances, leaving only an infant son as heir. When the one-year-old boy is appointed Sultan Hamengkubuwono V, a dispute ensues over guardianship. Diponegoro is again passed over, though believing he had been promised the right to succeed half- brother – even though such a succession would be illegal under Islamic rules. A series of natural disasters and political upheavals finally erupt into full-scale rebellion.

Dutch colonial rule becomes even more unpopular among local farmers – also because of tax rises, crop failures and among the Javanese nobles with the Dutch colonial authorities depriving them further of their right to lease land. Diponogoro is widely believed to be the Ratu Adil – the just ruler predicted in the Pralembang Jayabaya.

Mount Merapi’s eruption (1822) and a cholera epidemic (1824) precipitate increasing support for Diponegoro. In the days leading up to war’s outbreak, no action is taken by local Dutch officials although rumours of an upcoming insurrection abound. Prophesies and stories, ranging from visions from tomb of Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa to his contact with Nyai Roro Kidul, spread across the populace.

The beginning of the war sees large losses on Dutch, due to lack of coherent strategy and a commitment in fighting Diponegoro’s guerrilla warfare. Ambushes are set up, and food supplies denied to Dutch troops. The Dutch attempt to control spreading rebellion by increasing troops and and sending General de Kock to crush insurgency. De Kock develops a strategy of fortified camps (benteng) and mobile forces. Heavily-fortified and well-defended soldiers occupy key landmarks to limit movement of Diponegoro’s troops while mobile forces find & contain the rebels. From 1829, Diponegoro’s position weakens – 1st in Ungaran, then in the palace of the Resident in Semarang, before finally, he is forced to retreat to Batavia. Many troops and leaders are defeated or desert. Diponegoro is ultimately defeated and negotiations start (1830).

Diponegoro demands to have a free state under a sultan with him as Muslim leader (caliph) of Java. Invited (March 1830) to negotiate under a flag of truce, he accepts and meets at the town of Magelang but is taken prisoner (28 March) despite the flag of truce. De Kock claims having warned several Javanese nobles to tell Diponegoro to lessen his previous demands or that he would be forced to take other measures.

The circumstances of Diponegoro’s arrest are seen differently by himself and the Dutch. The former see arrest as a betrayal due to presenting a flag of truce, while the latter declare that he had surrendered. The event, is depicted separately by the Javanese Raden Saleh and the Dutch Nicolaas Pieneman, depicting Diponegoro differently in their respective paintings – the former visualizing him as a defiant victim, the latter as a subjugated man.

Immediately after his arrest, he is taken to Semarang and later to Batavia, where he is detained in the basement of what is today the Fatahillah Museum. He is then taken (1830) to Manado, Sulawesi by ship before moving to Makassar (July 1833) where he is detained within Fort Rottedam. Despite his prisoner status, his one wife Ratnaningsih and some of followers accompany him into exile and he even receives high-profile visitors including 16 year- old Dutch Prince Henry (1837).

Diponegoro also composes manuscripts on Javanese history and writes his autobiography, Babad Diponegoro, during his exile. His physical health deteriorates due to old age, and he dies (8 January 1855). Before his death, he requests to be buried in the Kampung Melayu, a neighborhood then inhabited by the Chinese and Dutch which follows, with the Dutch donating 1.5 hectares of land for his graveyard which today has been reduced to just 550 square meters. Later, his wife and followers are also buried in the same complex. His tomb is today visited by pilgrims – often military officers and politicians.

Diponegoro’s dynasty survives to the present-day – descendants from 17 sons and five daughters by three wives:

- Kedhaton,

- Ratnaningsih and

- Ratnaningrum,

with their sultans holding secular powers as governors of the Special Region of Yoghakarta.

A monument is erected (1969) in Tegalrejo, outside Yogyakarta, with military sponsorship where Diponegoro’s palace is believed to have stood. Under the presidency of Suharto, he is proclaimed (1973) a National Hero of Indonesia. Kodam IV Diponegoro, Indonesian Army regional command for Central Java Military Region, is named after him. The Indonesian Navy has named two ships after him – 1st of these was the lead ship KRI Diponegoro: a Sigma-class corvette purchased from the Netherlands. Diponegoro University in Semarang is also named after him, along with many major roads in Indonesian cities. Also depicted in Javanese stanzas, wayang, and performing arts – including the self-authored Babad Diponegoro. Increased militancy of people’s resistance in Java during the Indonesian Revolution sees the country gaining independence from the Netherlands with early Islamist political parties, such as the Masyumi, portraying Diponegoro’s jihad as a part of the Indonesian national struggle and by extension Islam as a prominent player in the formation of the new country.

During the Royal Netherlands state visit to Indonesia in March 2020, Dutch King Willem-Alexander returned the kris of Prince Diponegoro to Indonesia. The extraordinary gold-inlaid Javanese dagger previously was held in the Dutch state collection, but is now finally part of the collection of the Indonesian National Museum.